by Steve | Mar 12, 2008 | Uncategorized

Vietnamese pastor spreads God’s Word around the world

17 March 2008

By Kathy L. Gilbert, United Methodist News Service

The Rev Bau Dang would rather not talk about himself. He shies away from the spotlight.

He just made history by becoming the first Vietnamese American elected as a delegate to the 2008 United Methodist General Conference, the denomination’s top lawmaking body that meets every four years.

He finds it hard to believe that he was elected as a delegate to the 2008 General Conference, which will meet in Fort Worth, Texas, from April 23 to May 2.

And one more thing: He has just finished translating the New Testament into Vietnamese and published 10,000 copies at his own expense.

Vietnam’s communist government has issued a permit to the National Religious Publisher of Vietnam to print the translation, and now Christians in his home country are begging him to send them 100,000 more.

“To me, this is a miracle,” he said. “Praise be to God!”

His translation is spreading the Word of God throughout the country, which he is no longer able to enter.

Because of his stand for human rights, he has been placed on a list of people not allowed to enter Vietnam.

Midlife change Born in Vietnam, the son of a pastor, he served in the South Vietnamese armed forces and moved to the United States as a refugee after the war.

His friends thought he was going through a midlife crisis when he gave up a lucrative job as a manager for Xerox to become a United Methodist associate pastor.

Some of his Vietnamese pastor friends thought he had chosen the wrong denomination because no United Methodist church existed in Vietnam before 1975. “Some even thought that Methodism was a heresy!” he said.

He and his wife, Binh, both left jobs with Xerox in 1988. Since then, the Xerox operation they worked at has Vietnamese pastor spreads God’s Word around the world closed, but the church where he started as associate pastor – Wesley United Methodist Church in San Diego – has grown into a thriving ministry with four different languages spoken at six worship services to more than 400 people on Sunday mornings.

As Senior Pastor now, he plans services in English, Cambodian, Spanish and Vietnamese, “in whatever style fits each group”, he said.

Translating Old Testament He worked on his translation of the New Testament for 10 years. His knowledge of Greek, Hebrew, English and Vietnamese helped him with the task.

He also received training from the United Bible Society.

“I preach from the Bible every Sunday, and the version that we had was translated by missionaries in 1926 in Vietnam,” he said. When they came to the country, they were learning the language and hired a non- Christian to help with the translation.

“We had to live with that Bible for years and years,” he said. He felt uncomfortable with some text in the Bible and did not believe they were clear to the reader.

One example he cited is the passage in John 2, in which Jesus talks to his mother about turning water into wine.

“The way that passage is translated is very offensive to the Vietnamese culture,” he said. The translation made Jesus sound like he was speaking harshly to his mother. “Non-Christians say, ‘How can I believe in a God who responded to his mother so impolitely?’ and it turned them right away.”

Kathy L. Gilbert is a United Methodist News Service news writer based in Nashville, Tennessee.

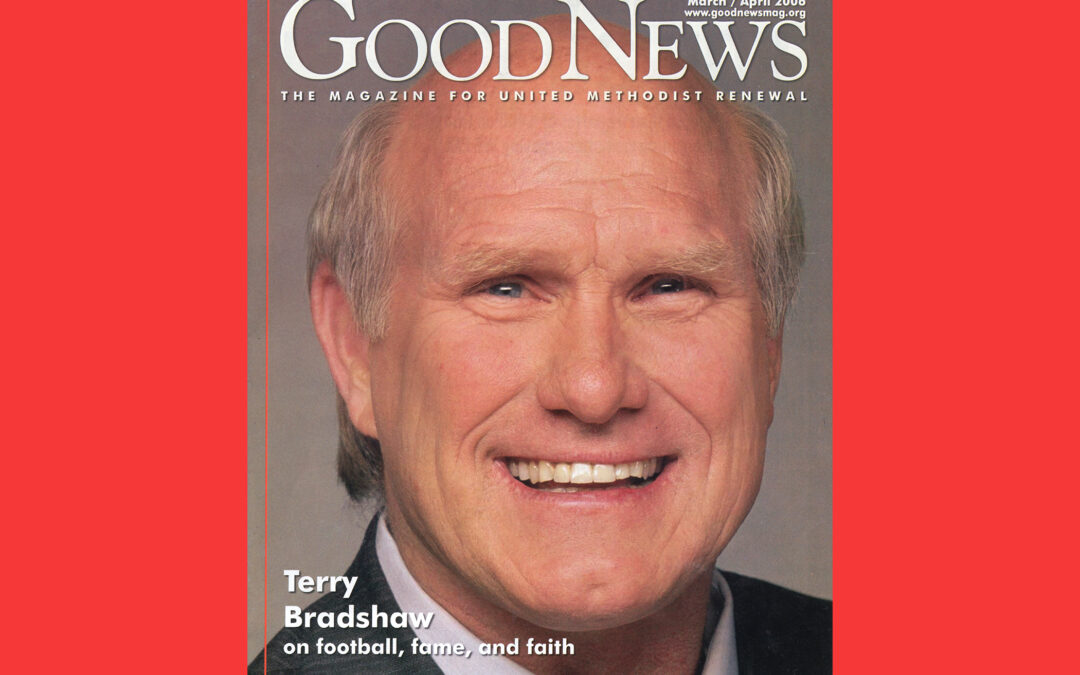

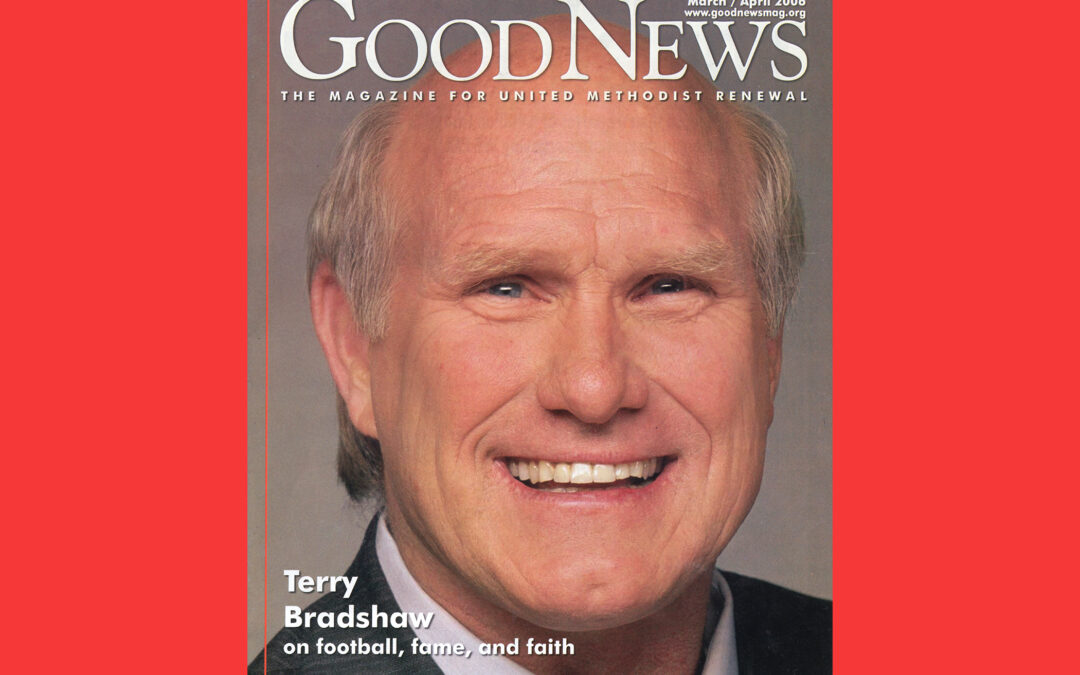

by Steve | Mar 9, 2006 | Archive - 2006

Archive: Tackling Terry Bradshaw

The NFL legend talks with Steve Beard

Good News, 2006

When I was growing up, I was infatuated with two NFL quarterbacks. One was the long-haired Kenny “The Snake” Stabler of the Oakland Raiders and the other was Terry Bradshaw of the Pittsburgh Steelers – the first quarterback in NFL history to lead his team to four Super Bowl championships.

Ever since he was chosen as a #1 draft pick player in 1970, Bradshaw has entertained sports fans as an athlete, broadcaster, and analyst. He led the Pittsburgh Steelers to six AFC championship games and eight straight playoff appearances from 1972-1979. Bradshaw, a two-time Super Bowl MVP, a four-time All-Pro, was inducted in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

I watch Bradshaw every Sunday afternoon as the co-host and analyst on “Fox NFL Sunday,” a four-time Emmy Award-winning NFL pregame show. His work on the program earned him two Sports Emmy Awards.

Since his retirement from football, Bradshaw has dabbled in show business, appearing both in feature films and television shows. He was the first NFL player to receive a Star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame.

Multitalented, Bradshaw has recorded four albums, two of which were gospel records nominated for Dove Awards (one of them with the legendary Jake Hess). He is an exceedingly popular motivational speaker and author of five books. I remember my parents giving me No Easy Game (1973) to read when I was just a kid. He was a great inspiration to me.

Four days before the Pittsburgh Steelers beat the Denver Broncos in the AFC Championship game to earn the right to play in Super Bowl XL (2006), I was able to catch up with Terry Bradshaw and ask him about three subjects he knows quite a bit about: fame, faith, and football.

What goes through your head when you see someone wearing a black and gold #12 jersey?

That’s pretty cool.

You are definitely not someone who glories in past accomplishments – as dramatic as they are. For example, you do not live in Pittsburgh. Do the glory days of the 1970s Steelers bring back good memories of a really great chapter of your life?

They do. And you’re right about one thing. I don’t dwell on yesterday. I’m living for today and planning for tomorrow. And that’s how I have always lived my life. I don’t live in the past. I don’t talk about my football accomplishments. I don’t do any of those things. To me, it just stirs up the past. And the past serves me no good. While I’m proud of it and realize how hard I worked to get there, it’s over. It’s over for me and I move on. But when I see that #12 jersey, like when I went back to Pittsburgh and saw my jersey was still being sold with my name on it, it does make you feel good.

It is not a secret that you are a Baptist. What is the most difficult thing about maintaining your faith in the spotlight?

Everybody’s Baptist here in the South except those who’ve been messed with. [Laughter.]

Here’s the first thing I always do at the end of the day: “Lord, forgive me, please.” A lot of forgiveness. There’s a lot of temptation. Not so much a woman-thing or a booze-thing, but just being-a-man-thing. You’re in the groups and you’re telling jokes and they’re laughin’ and gettin’ crazy. And then at the end of the day you pound your head and go, “Nice. Way to go, Terry. That’s just beautiful. Really, you’re really doin’ work for the Lord.”

It beats me up, everyday. I wish I were Billy Graham, but I’m not. I struggle. I fight. I go nuts. And the only time I’m really a good Christian is when football season is over and I’m able to get back in church around all my Christian family. And then I feel like I’ve been purified. But often I’ve said, “I’m just scum of the earth.” And I get so tired of being this weakling. I’m not a good example.

In your book Keep It Simple, you actually had your Christian therapist give us a sketch of your personality. Would you explain what he was able to do for you in relationship to your Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and depression?

Sure. Absolutely. I’ve said this a thousand times: “Everybody ought to have an analyst. Everybody.” And, you know, I still talk to my therapist, or whatever you want to call it. Still talk to him, still share things with him. Also, my preacher has become one of my best friends, and he helps me get past the guilt. Yeah, he’s a good friend of mine. And the church prays for me before I go off because they know I’m walking into that den of iniquity. It’s a struggle, man. I start off good. Then I get bad. Then I rebound, then I get worse. It just drives me up the wall. I oftentimes just go, “You know, some Christian you are.” And so many times I’ve ended the season and said, “I’m not going back. I’m not going to do this anymore. I’m sick and tired.”

I live on a ranch, and at nights I can see the stars and I’m just amazed that God loves me as much as he does when I’m such a pitiful example.

You have spoken about your reluctance to call yourself a Christian because you don’t want to be a bad example for the faith. Is that still what you believe?

It’s not something I dwell on. I don’t beat myself up anymore. One of the things I’ve done since I got saved and gone to therapy is not necessarily make excuses for myself anymore. My preacher’s helped me tremendously. I know God loves me. I know he forgives me. I know he’s upset with me and disappointed in me. But I don’t let my sin separate me from him like I used to. I don’t let that happen anymore. I’m not a good example, but I try to be.

I preached for the first time last year.

You did?

Yes, sir. In my speeches that I give I’m always making references to my faith. So I have slowly come out of that protective shell. I know how Christians are. We’re the worst people in the world. I understand why so many people say, “Why would I want what you’ve got. I’ve got the same thing. And look at you. You’re just as bad as I am.”

Is it different for those in the public eye?

That is a real struggle for people, not only in the public eye, but people that are not – it’s no different. It’s a struggle. And God knows it’s a struggle. I wish I could’ve walked with Jesus. Would I have been a Doubting Thomas? They saw the miracles performed. They saw him on the cross. They saw him gone from the tomb. And yet, they still had some doubts. If they had doubts and they saw it, you know, thousands of years later here we are. God says to us that we can get to heaven by accepting Christ by faith.

It’s so simple to get saved. It’s so simple, yet we look at the complexities of God and the wonders that he created and ask ourselves these questions, “How long did it take? How did he do it? Where did it come from?” So, as complex as it is to understand that – and he told us we’re not going to understand it – God made it a thousand times easier to become part of his family just by a simple profession of faith.

As Baptists are prone to ask, where are you planning on spending eternity?

Oh, I’m gonna be in heaven singin’ praises and walkin’ with Jesus and talkin’ with God and seeing the angels and being with my grandfather and my grandmother and all those that I love and my family that’s going to join me. Man, it’s going to be a celebration for eternity. That’s where I’m going to be. And I’m in no hurry to get there. But when I die, that’s where I’ll be.

Will there be country music in heaven?

There’ll be country music, and they’ll all sing on key.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Cover photo: Courtesy of FOX NFL Sunday (2006).

by Steve | Nov 15, 2005 | Archive - 2005

Archive: Chronicles of Narnia: “Values that the book embraced”

Steve Beard talks with Mark Johnson

November/December 2005

Mark Johnson has been producing films for more than twenty years. He has been involved in projects as diverse as Diner, My Dog Skip, Good Morning Vietnam, The Rookie, and The Notebook. Good NEWS editor Steve Beard spoke with Johnson about the production of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Is there much of an awareness in Hollywood of the writing of C.S. Lewis?

Mark Johnson: It’s interesting. l think everybody is aware of C.S. Lewis, and it’s amazing the number of people in Hollywood who read The Chronicles of Narnia. I don’t think anybody was saying, “We’ve got to make some movies based on C.S. Lewis’ work.” Tolkien was probably a similar type of aspect I suppose. But it’s clear for us to have made this movie the way that we did. And it’s a very expensive movie – I can’t reveal the budget – but it’s a big production.

Was there a temptation to make the movie radically different than the spirit of the book?

Johnson: Hollywood has ruined a number of books and a number of projects by trying to appeal to an audience that maybe the underlying rights didn’t appeal to or wasn’t aimed at. Everybody’s wary of Hollywood. When people see their favorite book, no matter what kind of book it is, being turned into a film, they are sort of wary. You’re hoping, “Oh gosh, l hope they didn’t ruin it.” Andrew and I wanted this movie to embrace the same values that the book embraced. And neither one of us was interested in any way of changing it.

In what ways was C.S. Lewis’ step-son, Douglas Gresham, involved in the project?

Johnson: Douglas was very involved in every stage from the script development to casting.

What was the greatest challenge in bringing this book to the big screen?

Johnson: J.R.R. Tolkien described everything in great detail. C.S. Lewis did just the opposite. He gave us a touchstone and then in your mind you create Narnia. You imagine, more specifically, what the White Witch looked like, as opposed to having everything described. And so there was a combination of having to be loyal to what he gave us, and then be able to use that as a jumping-off spot. And so people will say, “Gee, I thought the White Witch’s hair would be shorter.” That’s not because of anything C.S. Lewis said. That’s because of that White Witch existing in that person’s imagination.

It sounds as though director Andrew Adamson had his work cut out for himself.

Johnson: Andrew Adamson has taken what C.S. Lewis gave him and then has taken an artist’s imagination and has said, “Okay, the final battle is about a page and a half in the book. And yeah, it’ll be about 15-20 minutes in our movie.” So obviously a lot of it has to be made up. But Lewis was so smart in what he gave us was so to the point and so provocative chat it’s a great jumping-off start for an artist.

by Steve | Nov 15, 2005 | Archive - 2005

Archive: Chronicles of Narnia: Faithful Adaptation

Steve Beard talks with Michael Flaherty

November/December 2005

Michael Flaherty is the president of Walden Media, the film studio that is producing C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. He recently spoke with Good News editor Steve Beard about the upcoming movie.

Walden has adapted other books for children for the big screen. How is The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe different than other projects such as Holes or Because of Winn Dixie?

Michael Flaherty: It’s amazing. I don’t think it’s that unique because Walden looks for books that we can use to teach kids a lot about life and to get them to ask the big questions. So it’s like Holes or Because of Winn Dixie in that sense. This book has been around so much longer and it has such a much larger fan base.

Was there a temptation to change the setting of the book such as placing the story in modern-day America instead of Great Britain during World War II?

Flaherty: When we were interviewing, looking for writers and directors, we heard a lot of that. But the good news was we always made sure that everybody that was brought aboard wanted to make a faithful adaptation – that was the mantra. And once we met with director Andrew Adamson, who gave us the most incredible vision for how he would faithfully adapt it, everything fell into line. He made sure that everybody was on board with his vision. None of those intentions were there to put it in post-apocalyptic Los Angeles.

With his directing credits being limited to animated films such as Shrek and Shrek 2, was there a gamble in calling on the talents of Andrew Adamson?

Flaherty: They’re completely different kinds of movies. You know, he’d never done a live-action film before. But he knew exactly what he wanted to do and exactly how he wanted to bring it alive.

How did Walden secure the rights to The Chronicles of Narnia?

Flaherty: Over five years ago, my business partner Cary Granat and I were talking to Phil Anschutz about starting this company. Phil asked us for examples of films we wanted to make and Narnia was at the top of the list. That was something Phil had always wanted to do as well. So that was a real priority for the company. Right after they expired at Paramount – I think this was probably four years ago now at this point – we came in and got the rights to the film. We found screenwriter Ann Peacock and director Andrew Adamson. Disney came aboard after we had finished the script and the scouting and we put quite a bit of money into research to prove that we could successfully bring Narnia to life in a live-action film.

Many C.S. Lewis fans assumed that a Hollywood production of his books would diminish the spiritual nature of the stories. Did you anticipate that kind of reaction?

Flaherty: When we purchased the rights to these films, we had not released a single movie. So we had no reputation, no track record. And so we completely expected that. Let’s face it, Hollywood has a history, whether something has spiritual content or not, to completely gut and rewrite a lot of great literature. We bumped into this with Holes, which was our first movie out. A lot of people said, “I can’t believe that they’re making us watch another terrible Hollywood adaptation.” But then I think we earned some respect when people saw Holes and then Winn Dixie was another step along the way of showing people that we have great fidelity to original source material.

What is it about The Chronicles of Narnia – what C.S. Lewis described as the “gateway to a magical world” – that has intrigued audiences of all ages for so long?

Flaherty: It is such a beautiful story and simple story. It’s a great read. l remember myself and my brothers reading it really young in our years in grammar school. And I remember it being a read-aloud book even younger. The story is so easy to grasp for kids, but at the same time it’s so rich and complex for adults. We’re really happy because we feel like we have a movie for ages 6 to 106. What I love is just the messages of family and forgiveness and hope in a hopeless world. There are so many great themes. But best of all, here are two brothers and two sisters who stick together. And that’s the greatest family film in that sense – to see a family hold.

Lewis wrote a lot of letters to children. He addresses this and talks about how great fantasy heightens the readers’ sense of reality and responsibility. And I think that’s what we have here. So what’s amazing about it is it’s this incredible fantasy, but at the same time it’s this incredible window into our own personal lives this very day.

by Steve | Oct 17, 2005 | Uncategorized

Debating the old professor: C.S. Lewis and the advent of Aslan

By Elizabeth V. Glass

2005

| On a winter night in 1948, C.S. Lewis defended his argument for the existence of Narnia. No, he didn’t try to prove the reality of other worlds behind wardrobe doors. In fact, at that point he had not even written The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. But he did defend his case for the existence of supernatural realities, of things powerful and present that we cannot see—in other words, the existence of God. |

On February 2 of that year, Lewis attended a meeting of the Oxford University Socratic Club, an organization whose purpose was to debate issues related to Christianity. In the spirit of Socrates himself, the club was committed to “follow the argument wherever it led them.” The primary speaker for the evening was Elizabeth Anscombe, a brilliant young philosopher at Oxford, who read a paper attacking Lewis’ argument against naturalism in his recent book Miracles. (Naturalism is the belief that all that exists is the material world, and that all things can be explained without God and the supernatural.)

Although Anscombe herself was a Roman Catholic who embraced the existence of God, she found Lewis’ argument against naturalism fundamentally flawed. While Lewis lore has piled up like so many fur coats in his proverbial wardrobe, what is clear is that an exciting debate ensued that evening that has grown to legendary proportions over the years.

In his role as president of the Socratic Club, Lewis had gained a reputation as a formidable debater. But the results of the Lewis-Anscombe debate are themselves hotly contested. Some biographers recount it as “The Night That Lewis Lost.” Others, fearful of tarnishing his image as a scholar and defender of the faith, vehemently defend him. Still others claim that the debate was so disturbing to Lewis that he retreated from formal apologetics, turning to fiction instead. They cite the fact that it was soon after the debate with Anscombe that he began writing The Chronicles of Narnia. Did the celebrated Oxford intellectual and Christian apologist dodge the issues by sneaking into fairy tales, turning himself into the Old Professor of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe?

What emerges is a tangle of criticism and controversy. Like a battle on many fronts, there are multiple factors to weigh in interpreting Lewis’ contribution to academic as well as children’s literature. Some scholars turn their spectacles towards the actual issue that Lewis and Anscombe engaged, whether naturalism can be a coherent worldview. Other critics set their sights on how the encounter with Anscombe affected Lewis’ literary career. Did it shake his confidence in rational apologetics for the faith, or did he emerge personally unscathed but rhetorically defeated? To what degree was Anscombe on target in her criticism of his central argument in Miracles? Decades after the battle between Lewis and Anscombe, all of these queries recently held center stage yet again.

Among the spires of Oxford, England, the controversies of the legendary debate were brought to life by a dramatic re-enactment of the famous Socratic Club encounter. It was performed this past July at Oxbridge 2005, a summer convening of Lewis scholars and fans organized by the C.S. Lewis Institute and held every three years. The re-enactment gave the audience the opportunity to assess for themselves the merits of the arguments presented by Lewis and Anscombe. Adding to the historic significance of the re-enactment was the attendance of Professor Basil Mitchell, who knew Lewis, and succeeded him as President of the Socratic Club.

The script for the event, prepared by Dr. Jerry Walls, professor at Asbury Theological Seminary, and Phillip Tallon, graduate of Asbury Seminary and PhD candidate at St. Andrew’s University, Scotland, relied on several sources. Included by the editors were documents such as C.S. Lewis’ original chapter in Miracles against naturalism, Anscombe’s paper, Lewis’ revised chapter written after the debate, and notes taken by members of the Socratic Club. By weaving these sources together, Tallon and Walls were able to present a version of the debate true to the essence of the original. Staged at St. Aldate’s Church, Oxford, the script was convincingly delivered by British actors Robin Meredith and Christine Way. The performance itself served as a gateway into the world of Lewis and Anscombe, allowing the audience to step through the snow and join the lively professor alongside the cigar-smoking Anscombe.

Following the re-enactment, Gary Habermas of Liberty University interviewed world-renowned philosopher Antony Flew. Habermas has debated Flew publicly, developing a close friendship with him over the past few years. Professor Flew shared reflections on both the content and the significance of the 1948 debate. He attended Oxford and was present the night of the original debate at the Socratic Club. He recalled that Lewis seemed obviously distressed after the encounter, hurrying away across a bridge, while Anscombe exuberantly displayed a sense of triumph. The chat with Flew allowed the audience not only to hear first hand memories of the atmosphere of the debate, but also to catch a glimpse of the inner debate in Flew’s own recent life.

Flew is the son of noted Methodist theologian R. Newton Flew, but he is recognized as one of the most outspoken and influential atheists of our time. Lately, though, he has described himself as “an atheist with some very important questions,” and has shifted to deism. While deism is a form of belief in God, it does not accept special revelation like many major world religions would claim through their prophets and scriptures. Having represented the naturalistic worldview for so long, Flew’s transition to belief in God has caused a momentous stir in the academic community. In addition to making national news, the story even provided a joke for late night TV’s Jay Leno.

While Lewis and Anscombe went hammer and tong over the issue of whether reason requires a supernatural explanation, Flew was persuaded to belief in the supernatural by the imprint of intelligent design in the natural order. In other words, Lewis was firmly convinced that human reason can only be explained by the existence of the supernatural, while Flew was similarly persuaded by the evidence for ultimate reason and design in our universe. In this dramatic transition of thought, Dr. Flew exemplifies the spirit of the Socratic Club in following the argument wherever it leads, even after decades of embracing an opposing worldview.

Although Professor Flew now affirms the existence of God, he cited doctrines like the belief in hell into explain his rejection of Christianity and other major religions. At the conclusion of the interview with Flew, a new debate ensued that was much in the spirit of Lewis. Beginning with Dr. David Baggett of King’s College, Pennsylvania, a line of challengers rebutted Flew’s statements denying the plausibility of Christianity. The questioners included Peter Kreeft, noted Lewis scholar and professor of philosophy at Boston College, and Charles Colson, who had presented at the conference earlier in the week. Almost 50 years after the night at the Socratic Club, naturalism and supernaturalism again held the floor, stirring a lively exchange. For now, Flew remains unconvinced of the plausibility of special revelation as it is understood in Christianity.

If the dialogue with Antony Flew provides a snapshot of the contemporary dynamics of the debate, how should we portray the significance of the original Lewis-Anscombe encounter? Were The Chronicles of Narnia C.S. Lewis’ means of running away from reason and escaping into fantasy? Philosopher Victor Reppert doesn’t think so. He recently addressed the question in an essay published in The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy. Reppert establishes the point that far from creating a split between faith and reason, Lewis actually integrates them in his famous stories. Comparing one of his most quoted arguments in Mere Christianity with portions of The Chronicles of Narnia, Reppert finds that Lewis utilized the medium of children’s fiction to communicate the same truths found in his philosophical writings. To illustrate this fusion of reason and imagination, Reppert listens in as the Old Professor evaluates Lucy’s story of having visited another world through the wardrobe.

“Logic!” said the professor half to himself. “Why don’t they teach logic in these schools? There are only three possibilities. Either your sister is telling lies, or she is mad, or she is telling the truth. You know she doesn’t tell lies and it is obvious that she is not mad. For the moment then and unless any further evidence turns up, we must assume that she is telling the truth (LWW, Chapter 5, p.131 and The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy, 266).

In this passage, Reppert discovers that Lewis is using essentially the same argument in two venues. In Mere Christianity, Lewis argued that three possibilities emerge from Jesus’ claim to be divine: either he was a lunatic, a liar, or he was telling the truth. And, as described above, the scene in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe employs the same reasoning about Lucy’s unbelievable journey into Narnia.

What, then, may we conclude from this? The claim that Lewis simply backed into his wardrobe just doesn’t hold. Reppert even suggests that “the Narnia books can themselves be seen as works of broadly Christian apologetics.” This implies that Lewis intentionally infused his fiction with rational portrayals of transcendent truth. Far from splitting reason and faith, as his critics suppose, Lewis brilliantly synthesized the two.

It is only when we understand his commitment to myth as an appropriate illumination of truth that we fully appreciate the scope of his harmonization.

Lewis understood myth as, “at its best, a real though unfocused gleam of divine truth falling on human imagination.” This description protects the concept of myth from misunderstanding. Lewis makes clear that myth is not a falsehood, nor is it underdeveloped “misunderstood history” formed by a backward group of people to convey their identity and beliefs. Instead, Lewis finds that myth—storytelling that uses the imagination—can sometimes communicate Truth more wholly than other avenues. Myth puts hands, feet, and sometimes even paws on abstract principles, making them easier to see, mimic, and listen to. It binds together right thinking with right action by whispering stories of heroes and traitors. And anytime truth is present, reason is present; so it is possible for made up stories to reflect that “unfocused gleam of divine truth” in ways that exercise rational discernment.

At the end of the day, Lewis’ motives for writing The Chronicles of Narnia are most clearly found when Lewis is primarily understood as literary scholar. The debate with Anscombe merely served to better hone his arguments in his book Miracles. For Lewis, there is creativity in the call to serve truth. Known for enjoying walks around Oxford, Lewis established well-worn paths through many different terrains, whether group debate or popular writing, philosophical treatises or literary criticism, children’s books or epic poems. By also becoming familiar with a variety of terrains, we are best equipped to guide others to Narnia. Truth may be clothed in myth, as Lewis famously dressed it, or in scientific evidence, like that which persuaded Antony Flew. However its advent comes about, following the argument wherever it leads is similar to walking the Road to Emmaus: Truth will appear beside us, much as Aslan did to the children who journeyed through the wardrobe.

Elizabeth V. Glass was a student at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky at the time of this article being published.