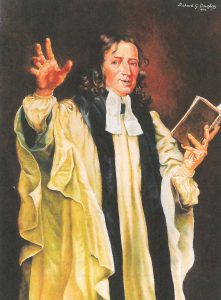

Dr. Richard Douglas painted this portrait of John Wesley in 2003. According to the late Dr. Kenneth Kinghorn, the portrait shows “Wesley preaching without notes, while holding his famous field Bible….He wears no wig, and his natural hair had a slight auburn tint” (John Wesley: An Album of Portraits and Engravings, Empethpress.com). This portrait hangs at Asbury Theological Seminary.

By Donald Haynes-

For the first time since the young United Methodist Church struggled with our theology in 1968 and again in 1988, we are once again asking, “What do the spiritual progeny of John Wesley believe?” Just as importantly, however, is the unusual linkage that Wesley (1703-1791) made between what we believe and how we live. Wesley’s disagreement with Lutheran and Calvinist theology was that while we are saved by our faith in God’s grace, we are saved to “faithfulness.” He called it “holiness of heart and life.”

In the coming months of 2018-2020, United Methodism must examine our roots of what we believe and how that belief affects our morals and ethics. Whether we are “progressive” or “traditional” in our theological bent, our present way forward must be done in the context of historic Wesleyanism. To use seminary terminology, what is our Wesleyan relationship between orthodoxy and orthopraxy? We must be true to who we are. So what is our “consensus of faith” rooted in the Methodist movement within the Church of England and, even more importantly, what is our evangelical heritage in American Methodism, United Brethren, and the Evangelical Association?

In the important but often overlooked book, John Wesley’s Experimental Divinity by Dr. Robert Cushman of Duke Divinity School, we see early Methodists finding common affirmation to the Latin term “consensus Fidelium” or “consensus of faith.” That is, “what do we children of Wesley hold in common; on what can we agree to be our theological heritage?” This will never mean that every United Methodist has the same conscience regarding what is right and what is wrong in the sight of God. Truly, we are called to Wesley’s insistence that we “love alike” even when we do not “think alike.” But that “catholic spirit” does not give us the freedom to “love God and do what we please.” That is called “antinomianism” (anti means “against” and nomos means “the law”). Antinomianism disengages doctrine from a disciplined life.

Holy living was a dimension of being a Christian that Wesley retained from his own journey that began in his college days at Oxford in 1725 and continued until the marvelous night of Aldersgate on May 24, 1738 when he “felt his heart strangely warmed.” While it was not until that night that he felt the inner peace that comes with knowing our sins forgiven, Wesley had practiced Christian discipline (“holy living”). He calls it “the habitual disposition of the soul which in the Sacred Writings is called ‘holiness,’ and which directly implies the being cleansed from sin, ‘from all filthiness both of flesh and spirit,’ … being so ‘renewed in the image of our mind’ as to be ‘perfect as our Father in heaven is perfect’” (Matthew 5:48).

As Dr. Randy Maddox of Duke Divinity School has so clearly outlined for us, Wesley’s grace theology was not totally the divinely initiated grace that the Calvinists believe in. Rather it was what Maddox calls in his book by the same title, “responsible grace.” That is, Wesley insisted that God first loves us as we see in John 3:16: “God so loved … that God gave … that we might have eternal life.” However, we are free to accept or reject God’s love and, if we accept God’s initiating love, we are required to practice a disciplined response, just as any responsible relationship does.

Bust of John Wesley from the famous English artisan Enoch Wood (1759-1840). A UMNS photo by Kathleen Barry.

John Calvin (1509-1564) believed that grace is irresistible; Wesley believed that we have the free will to resist or reject God’s love. Maddox calls this “synergism.” In accepting God’s grace, we must live “in sync” with Jesus. John the Elder wrote in his second epistle, “This is love: that we walk in obedience to his commands. As you have heard from the beginning, his command is that you walk in love” (II John vs. 6). In his third epistle, John wrote to Gaius, “I have no greater joy than to hear that my children are walking in the Truth” (vs. 4). All these and many more scriptural references document Wesley’s insistence that God’s initiating grace is to be met with our responsive faith; so it is that we are saved by God’s grace through our responsive faith.

The “consensus of faith” that Cushman delineated correctly identifies three “faces of grace.” First of all is God’s preparing grace that in older language was called “prevenient grace.” Prevenient grace is indeed at God’s initiative. Then, if we might be colloquial, “the ball comes to our court.” If we respond affirmatively, we reach what Wesley called the “porch of salvation” and we repent of our sins. But repentance is not remorse; it is an active work of the Holy Spirit witnessing with our spirit that our confessional repentance is met with what Jesus illustrated as the “waiting father” in the Parable of the Prodigal Son. We are changed. That is, God meets our response to his love with what Wesley experienced at Aldersgate — a strangely warmed heart. It is the second dimension of what Wesley called the “scriptural way of salvation.” The revival movement of the 19th century codified this as “being saved.” Paul describes it in Romans 8 as “His Spirit witnessing with our spirit that we are children of God, and if children, then heirs, heirs of God and joint heirs with Christ.”

Our consensus of faith for Wesley and for early Methodism was that we are called by God’s initiating, preparing grace, we respond with repentance that is met with our heavenly Father’s love. Then, our doctrine moves to a life of discipline and obedience to the leading of the Holy Spirit for changed lives. Wesley here taps into his Anglo-Catholic heritage of what he called “inner and outward holiness of heart and life.” This dimension of our Christian journey lasts the rest of our life with its several seasons and many twists and turns. For a century we called it “sanctification.” Then, for a century, we dropped it from our teachings. More recently, we call it “perfecting grace.” Walking with Jesus, we grow in grace. Wesley called it “grace upon grace.” He even defined the discipline by which we walk this journey as a “means of grace.”

Wesley’s list of the “means of grace” varied from time to time, but always included prayer, searching the scriptures, frequent communion, and regular church attendance. Along the way, we are either dramatically or quietly filled with the Spirit, becoming what Paul called “in Christ.” Wesley preferred clinical language over courtroom or juridical language. He called Jesus “the great physician of souls” and called being saved, “taking the cure.” Faith was not a set of beliefs, but for Wesley it was “a living, saving faith,” adaptable to our life seasons and circumstances. Clearly, our common faith heritage is that we must forever keep linked the beliefs of the head with the confirming testimony of the heart. Orthodoxy must be linked with living a life that “becomes the Gospel.” This means self discipline – and as Wesley reminded his followers, being a Christian means “denying ourselves (certain liberties of indulgence) and taking up our cross daily.”

Dr. Cushman died in 1989 with a posthumously published warning: “Wesley’s ‘experimental divinity’ had lost currency and by the latter part of the 20th century was not regarded as essential, and affirming it was often received as controversial. Meanwhile the spectacular decline of the past decade and more may suggest that many have wearied beyond endurance with a church that manages mainly ‘the form of godliness that is doctrinally shapeless.’”

Frighteningly, many United Methodists today are not comfortable with being called “evangelical.” However, the “consensus of faith” in our heritage is unequivocally evangelical. Immediately following the Christmas Conference in 1784, these words were printed in the prototype of our Book of Discipline: “Far from wishing you to be ignorant of any of our doctrines, or any part of our discipline, we desire you to read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest the whole….”

The “consensus Fidelium” was, and should still be, our consensus of faith and faithfulness, our common consent to what the early preachers called “Wesley’s little body of divinity” or his “Scriptural Way of Salvation.”

Donald W. Haynes is a retired United Methodist clergyperson from the Western North Carolina Annual Conference, author, and adjunct professor of United Methodist Studies at Hood Theological Seminary.

0 Comments