By Kenneth Tanner

“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14 ESV)

“Therefore he had to be made like his brothers in every respect, so that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God, to make propitiation for the sins of the people” (Hebrews 2:17 ESV)

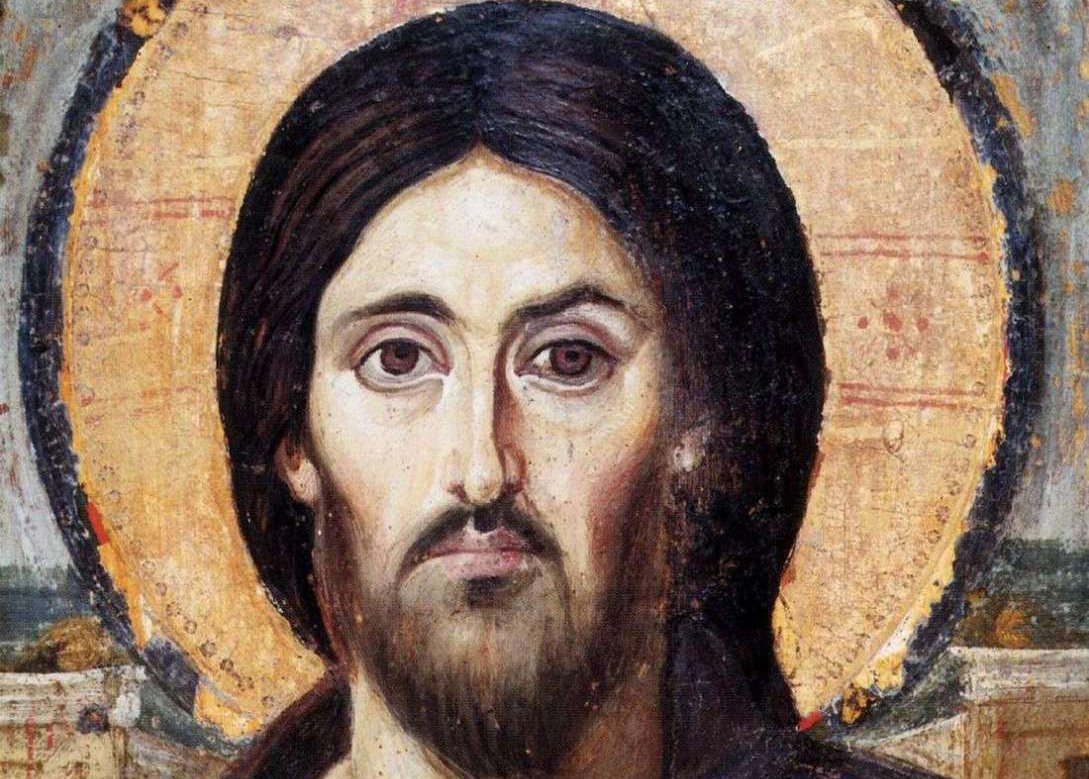

On a wall in the chapel of the Saint Catherine’s Monastery, a remote wilderness abbey at the base of Mount Sinai in Egypt, hangs an icon.

It’s not a poster of Brad Pitt or a reproduction of the Apple or Microsoft logo. This is a religious icon, perhaps the oldest in the world – a special painting the first Christians called a window into heaven.

This figure of Christ Pantocrator, or Christ the Ruler of All, is no ordinary icon. No surviving icon of its era looks anything like it. It seems fresh, as if painted yesterday.

Believed to have been given to the desert monastery in the mid-sixth century by the Byzantine emperor Justinian, it survived a period when icons were destroyed in many urban churches, was preserved against deterioration in the arid climate, and was secured from invaders by an order of protection the prophet Muhammad himself granted after the monks of Saint Catherine’s gave him shelter and hospitality.

The icon shares sixty-three points of precise alignment with the image of Jesus “burned” into the Shroud of Turin, five times the number of alignments needed to match fingerprints.

For many, this is the closest thing we have to a photograph of God.

Note the difference between the left side of the face (in which some see evidence of Christ’s torture and passion) and the right side (in which some discern his transfigured, resurrected radiance).

The icon tells the story of Good Friday and Easter.

The eyes stand out. Something about them is not quite right. For some, they have an unsettling quality. One of my childhood friends had a lazy eye. He was wonderfully unconscious of his difference, but I often was distracted by it. More frequently than I’d like to admit, I caught myself staring.

The more time I spent in prayer looking at this unique image of Jesus – the Pantocrator – the more the asymmetry of the eyes troubled me. I pondered why the artist would paint Jesus with a physical “imperfection.”

Eventually I realized this was not a problem with the artist or the image but rather a limitation of my imagination, a failure to see everything there is to see in Christ. After all, the word became flesh in Jesus (John 1:4) and was made like us in every respect (Hebrews 2:17).

Jesus took on everything it means to be human. One early Christian pastor taught that “what has not been assumed has not been redeemed.” Jesus grew tired, donned a cloak against the piercing cold and burning sun, could catch a virus or suffer a wasting disease, and if all that is true, he might also have borne some physical “defects.” Isaiah’s prophecy of the suffering servant warned us that Jesus had “nothing beautiful or majestic about his appearance, nothing to attract us to him” (53:2b NLT).

Still, I discovered it wasn’t just a matter of accepting that Jesus might have had physical imperfections. I had never absorbed into my heart the reality that the divine became one with matter in Jesus. Real flesh, real bones, real heart.

My encounter with the Sinai Pantocrator helped end my inherited mental image of Jesus as a stick figure in a Bible story – a Sunday school flannelgraph character – and experience the full-blooded actuality of how things are in Jesus Christ; even the possibility that the sinless one’s participation in our nature involved bearing physical infirmities, just as daily he grew thirsty, hungry, and weary.

Icons of Christ help us consider that Jesus is no abstraction – no mere thought, no matter how beautiful; no protagonist in a children’s story told to make us feel better – but the express image of the unseen all-holy God made vulnerable (Colossians 1:15), made like us “in every way.”

We see in Jesus the sacred reality of our humanity as God intended it from the beginning; his was the first human life to fulfill that intention. The Sinai icon helps us comprehend that we become most truly human when we embrace the humanity of God in Jesus Christ.

Embracing the humanity of God, icons help us visualize such an incredible possibility; that we might, by grace, become transfigured partakers of the divine nature in clay (2 Peter 1:4).

I have a sort of odd pastoral practice. I keep small wood-mounted reproductions of this Sinai icon in my backpack to give to strangers and friends. I started this about ten years ago on Chicago’s trains, subways, and buses. My commute was four hours round trip. Eventually folks figured out I was an undercover man of the cloth, commuting and working just as they did every day – someone imperfect enough that they eventually came to share with me their questions about God.

The icon gave me a way to show them the gospel and allowed me to use fewer words when I did so. Fifteen hundred years after its creation, the icon still hangs in the shadows of the mountain on which God forbade the worship of idols.

The reason this isn’t ironic is that icons are not idols. Idols are objects that we make and worship in place of the living God. In Jesus Christ, God has acted to make a perfect image of himself (Hebrews 1:3).

God has made Jesus the “visible image of the invisible God.” When iconographers depict Christ in the icons they write – in their parlance, icons are “written,” not painted – the writers are not fashioning a god for themselves but rendering an image of what the Father, Son, and Spirit have already done in the incarnation of the one God in Jesus Christ.

It is not idolatry that God became flesh in Jesus, and it is not idolatry to depict what God has done and hang these depictions in our homes and houses of worship just like we hang family photos or images of contemporary leaders. We would never think to tear such images up or deface them, because these pictures represent the people we love. Almost no one worships these depictions. Christians do, however, worship a God who clothed himself in clay, in the same material stuff with which he made our ancestors in his image in the Garden of Eden.

Women and men are made in the image of God, female and male together bearing all that is in God, and so it shouldn’t surprise us when our incarnate Lord looks like us. The Sinai icon reminds us that we are one with him and he is one with us.

Ponder with me for a moment the mystery that we’ve entered when we encounter Christ in the Gospels . . .

When Jesus is on the Sea of Galilee with the disciples, and storm winds and waves frighten even seasoned fishermen, we find the God who made the waves, the wind, and the wood the boat is crafted from – who made everything and holds everything together – tired and asleep in the hold of the ship.

God is asleep on a boat, even though our first thought as readers is that, of course, Jesus, a mere human, is napping (and that is true, too).

When the disciples awaken Jesus and he surveys the situation (and their hearts), he rebukes their fear, and then a mere man stands up on two feet in a vessel sloshing with lake water and speaks: “Peace, be still.”

Someone just like the rest of the disciples – with breathing lungs and a beating heart, sleepy and finding his sea legs – makes the wind stop gusting and turns the waves to glass with his words. As readers, we think Jesus is God and this awe-inspiring ability fits his divinity, but Jesus is also merely human, no more special in his biochemistry than anyone else in that boat on a sea gone wild.

When we read every story about Jesus with the sort of contemplation that icons allow – realizing this protagonist is in every moment God “all‑in” and human “all‑in” – we begin to discern that something has happened forever in God and something has happened forever in us, because the Son who breathed the stars into fiery existence and set their courses in the sky, who made the orchid and the hummingbird, humbled himself and was made like us in every way: weary, thirsty, hungry, aching, longing, striving, rejected, fallen, marvelous clay that we are, that we might be as he is, as God from all eternity. World without end.

The Sinai icon reminds us that in Jesus Christ, God leaves fingerprints, leaves DNA , wherever he goes (Jesus is human without measure); that Jesus breathes the spirit of the Father’s loving-kindness on all things (Jesus is divine without qualification).

His blood, his touch, his stops of breath reconcile the creator and the clay that as female and male alone in all creation bears the image of God.

Jesus walks with us, walks as us now, and we participate by our prayers, by our touch, by our faith and compassion – sometimes even by our blood – in the renewal of all things.

We see the likeness of Jesus in every human. Would that they might behold in our faces the icon of his vulnerability, self-sacrificial love, and resurrection in this wild, wonderful world he became human to restore to life without end.

Kenneth Tanner is pastor of Church of the Holy Redeemer in Rochester Hills, Michigan. His writing has appeared in Books & Culture, The Huffington Post, Sojourners, National Review, and Christianity Today. This essay originally appeared in Disquiet Time: Rants and Reflections on the Good Book by the Skeptical, the Faithful, and a Few Scoundrels (Jericho Books). It is reprinted by permission. This article appeared in the January/February 2015 issue of Good News. Artwork is Christ Pantocrator from Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai.

0 Comments