By David Watson –

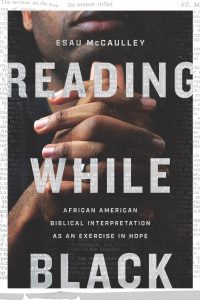

The Rev. Dr. Esau McCaulley is an Anglican priest and Assistant Professor of New Testament at Wheaton College. While studying at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, he received his PhD under the direction of the eminent New Testament scholar N. T. Wright. McCaulley’s new book, Reading While Black, has engendered considerable discussion both in the church and the academy, and with good reason. It is an informative, thought-provoking, sometimes convicting work that brings together his personal story as an African American growing up in the South, the larger tradition of biblical interpretation in the black church, and insights of historical and literary exegesis. Allow me to walk through the chapters and the topics addressed in sequence.

1. “The South Got Somethin’ to Say.” McCaulley marks out the terrain of what he calls “Black ecclesial interpretation” of the Bible. This tradition stands amidst other traditions, namely white progressivism, white evangelicalism, and African American progressivism. The black church tradition he describes is theologically orthodox, a characteristic it shares with white evangelicalism. In this sense it differs from white and African American forms of progressivism, which have tended toward theological and biblical revisionism. Yet for all their commonalities, the black ecclesial tradition and white evangelicalism differ in that the latter has often failed to confront matters of racism and injustice, and at times has perpetuated them. McCaulley highlights a style of biblical interpretation that maintains continuity with historic Christian doctrines and is located within the experience of African American Christians who have struggled with injustice and oppression.

2. “Freedom Is No Fear.” This chapter deals with the matter of policing, the relationship between African Americans and the police in the United States, and biblical texts that can provide insight into just policing. He takes up Romans 13:1-2, arguing that it does not represent a call to absolute obedience of government authorities, particularly unjust ones. God raised up Pharaoh (Romans 9:17), but then used Moses to defy him and free the Israelites from unjust rule.

McCaulley argues that Romans 13:1-2 is “a statement about the sovereignty of God and the limits of human discernment.” We are allowed to condemn evil like the prophets did, but we also may not know how we are functioning in God’s wider purposes, and therefore “we cannot claim divine sanction for the proper timing and method of solving the problems we discern.” McCaulley then offers a brief discussion of policing in the Roman world of the early Christians, and from there he moves into a discussion of a Christian theology of policing. As Christians, we should work toward the formation of governments, including policing policies, that allow people to live without fear. This has not been what we have done in the United States, and Christians must call upon the state to do better.

3. “Tired Feet, Rested Souls.” McCaulley takes up the issue of the relationship between church and government in this chapter. African American Christians, McCaulley says, “have never had the luxury of separating our faith from political action.” He examines two texts, Romans 13:1-7 and 1 Timothy 2:1-4, which instruct Christians regarding the following duties: “(1) submit to the state, (2) pay your taxes, and (3) pray for those in leadership.” None of these duties is wrong, he says. Rather, by themselves they are simply inadequate. The testimony of Jesus shows us that it is at times not only permissible but necessary to criticize the government. Jesus criticized both Herod’s character and his politics. We can also find criticism of the political order in the Sermon on the Mount, Paul’s writings, and the Revelation to John. Black Christians who criticize the public order have biblical warrant for their actions and they have an ally in the God of Israel.

4. “Reading While Black.” McCaulley discusses the ways in which African American Christians often face opposition from both the ideological left and the right. On the one hand, there are those who restrict the Bible to the saving of souls and neglect its power to critique unjust social structures. On the other hand, there are critics of Christianity who say that the Bible can do nothing for them anyway, that its teachings do not lead to a more just society. McCaulley then turns his attention to themes in the Gospel of Luke, which “contains a vision for the just society transformed by the advent of God that speaks to the hearts of Black Christians.” Jesus’ teaching and ministry, as depicted in Luke, “involves nothing less than the creation of a new world in which the marginalized are healed spiritually, economically, and psychologically.” Despite the fact that many people seem to miss it, the Bible provides a powerful warrant not just for the saving of souls, but for the liberation of bodies.

5. “Black and Proud.” In this section, McCaulley takes up the relationship between black identity and the Bible. While some claim that Christianity is a “white man’s religion,” this claim ignores the origins and early development of Christianity in the Middle East and North Africa. He also uses the examples of the half-Egyptian, half-Jewish Ephraim and Manasseh (Genesis 48:3-5) to demonstrate that it was always God’s plan to develop a community of different ethnicities. As he puts it, “African blood flows into Israel from the beginning as a fulfilment of the promise made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” (italics original).

McCaulley draws upon Psalm 72 to demonstrate that God envisioned a just, multiethnic kingdom that would extend throughout the globe. These promises are fulfilled through Jesus, and we see examples of the multiethnic nature of Jesus’ kingdom in Simon of Cyrene (Mark 15:21) and the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26-40). He closes this chapter with a discussion of the vision of Revelation 7:9-10, in which people of every nation, tribe, and language stand before the lamb and the throne.

6. “What Shall We Do with this Rage?” As the title suggests, it deals with the suffering of African Americans and the emotions such suffering produces. He begins by discussing the anger expressed in the prophets and psalms. The discussion of Psalm 137 is especially poignant here. Next he takes up the prophetic warnings against endless cycles of violence. “The miracle of Israel’s witness is that the Old Testament could imagine something beyond blood vengeance” (italics original).

God’s answer to human suffering, including black suffering, “is to enter that suffering alongside us as a friend and a redeemer.” God has done this through the cross, and thus broken the cycle of vengeance and death. McCaulley ends the chapter by considering the biblical themes of the resurrection, ascension, and final judgement as necessary for dealing with black anger and pain.

7. “The Freedom of the Slaves.” This chapter addresses biblical passages that discuss slavery. Yes, he notes, there are passages in the Bible that, when taken in isolation, one could read as supporting the institution of slavery. Nevertheless, he holds, “the Old Testament and later the New Testament create an imaginative world in which slavery becomes more and more untenable. Stated differently, God created a people who could theologically deconstruct slavery.” There are passages in Scripture, he argues, that positively describe God’s intents and purposes for our lives. Other passages, however, simply mitigate the harmful effects of human sinfulness. He addresses texts dealing with slavery in both Testaments and provides exegetical insights that can help us to understand these texts in relationship to a broader Christian ethic that categorically rejects slavery.

8. “An Exercise in Hope.” McCaulley emphasizes here that his aim has not been innovative, but rather to give expression to a tradition that has preceded and formed him. There are rich insights in this tradition worthy of further discussion and exploration.

In the epilogue, he reflects upon various strands of African American biblical interpretation. He notes that African American biblical interpretation is clearly socially located, but in this sense it is no different from any other form of biblical interpretation. Further, he argues, while some biblical interpretation focuses on personal transformation to the exclusion of social transformation or vice-versa, the tradition of African American biblical interpretation focuses on both. He refers to liberative, conversionist, and holiness strands of biblical interpretation, all of which are represented in various ways in this book.

Issues of race are at the forefront of public discourse in the United States today. These issues are important and complex. As Christians, we cannot avoid the places in the world where there is pain, anger, suffering, and injustice. In fact, we are called into them. For white Christians, however, it can be difficult to know how to enter into these conversations around race. Further, while there are myriad voices espousing secular theories regarding how to deal with racial injustice, as Christians we will be more concerned with the guidance of Scripture and the discernment of brothers and sisters in Christ. For those who want to learn from Scripture about matters of race and justice, this book is a gift.

Dr. Esau McCaulley

Here is a brother in Christ sharing his heart, sharing the fruit of his labor as a scholar and priest, inviting fellow Christians into a conversation that is desperately needed in the American church. He is committed to the faith once and for all entrusted to the saints. He is committed to life in keeping with the witness of Scripture. He shines light on a tradition of scriptural interpretation that has sustained African American Christians across centuries of hardship and enlivens them even today. Let those who have ears to hear, listen.

There are exegetical conclusions in the book with which one might take issue. For example, I had a hard time following the discussion of Romans 13:1-2 all the way through to the conclusion he reaches. On the whole, though, McCaulley’s exegetical moves are convincing. I was particularly interested in his analysis of policing in the ancient Roman world, a topic which, as he notes, merits further and deeper discussion. I also found the discussion in chapter 7 of texts dealing with slavery extremely helpful. In fact I plan to draw upon his analysis the next time I teach on Paul’s letters. The book is full of rich and thought-provoking exegetical insights.

As a New Testament scholar, I appreciate his earnest wrestling with the text. He does not sugar-coat the difficulties we find therein, but he draws out the redemptive messages so pervasive in Scripture when we read with an eye to its canonical narrative of salvation.

If you are a pastor or layperson looking for a way to engage fellow Christians on issues of faith and race, I recommend Dr. McCaulley’s Reading While Black. It is an accessible, biblically-based, and challenging discussion of these issues so important to the integrity of our Christian witness.

David F. Watson is a professor of New Testament and the Academic Dean at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of several books, including Scripture and the Life of God (Seedbed).

0 Comments