Faith, Love, and Praise: The Nicene Creed and Liturgical Formation —

By Jonathan A. Powers –

Words matter. Think of the old saying: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” We may want that to be true, but deep down we know it isn’t. Words do hurt. They also heal. They shape how we see the world, how we understand ourselves, and how we relate to others. Words have power. They can tear down or build up, distort or clarify, wound or bring peace.

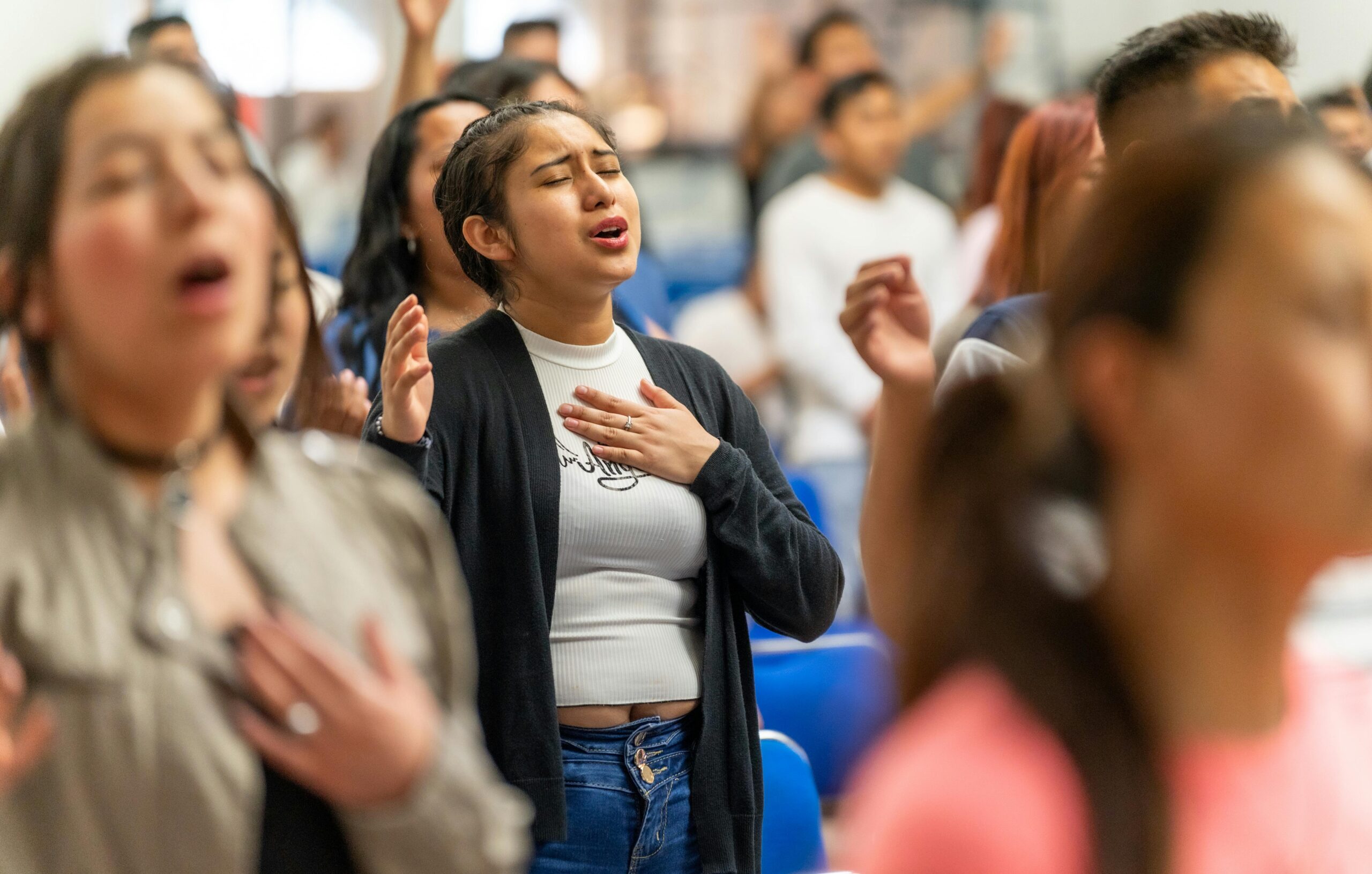

Words matter when it comes to the Christian faith, too. The words we use as Christians aren’t just filler. They guide us, encourage us, and form us. When words are placed on the lips of the church, they help shape identity, anchor faith, and express devotion to God. The prayers we pray, the songs we sing, the Scripture we hear, and the creeds we confess all aid in forming what we believe about God and how we live in response.

God-given revelation recognizes that the Bible is our final authority in all matters of faith and practice as the inspired word of God. Though Methodists draw on the Wesleyan heritage of discerning truth through the lenses of Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience, we keep Scripture primary. Rooted in the early church’s response to heretical teachings, the creed clarifies orthodox belief and provides a theological foundation for Christian discipleship. In addition to its importance as a doctrinal statement, the Nicene Creed functions as a foundational liturgical act. When practiced faithfully, saying the words of the creed together as the church can be a means for forming hearts, grounding worship, and uniting the church in the shared story of God’s redeeming love.

Across the centuries of the church, the Nicene Creed has remained an indispensable component of its liturgical worship. As a liturgical act, the Nicene Creed embodies the church’s living memory and theological inheritance. When recited in the liturgy, the creed serves not merely as a reminder of past controversies or as a dogmatic exercise, but also as a formative practice through which the church proclaims its faith anew. Rooted in the trinitarian grammar of Scripture, the creed reflects the church’s understanding of God’s nature and work — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit — in creation, redemption, and sanctification. It safeguards the central confession that Jesus Christ is both fully divine and fully human, upholding the mystery of the Incarnation and the unity of the Godhead. In affirming these truths, the words of the creed invite the church to rehearse the gospel story and to participate in the church’s mission as it bears witness to the God who has made Himself known in Jesus Christ and who continues to dwell with His people by the power of the Holy Spirit. Through the creed, the church enters a divine mystery, aligning heart, mind, and voice in shared confession and praise.

It is important, therefore, to understand the value of the creed as a liturgical act that gives voice to the church’s faith in the context of gathered worship. Spoken as prayer, the creed does more than communicate theological content — it forms the hearts and minds of those who confess it. The words of the creed, repeated in worship across generations, become a shaping force in the life of the church, binding belief and practice together in a rhythm of faithful devotion.

A proper appreciation of the creed as a liturgical act must begin with a clear understanding of what liturgy is and why it holds significance in the life of the church. The word liturgy comes from a Greek term meaning “public work” or “the work of the people,” reminding us that worship is not a private activity but a communal offering, something we do together as the body of Christ. Liturgical theologians often point to an ancient Latin phrase to highlight the deep connection between worship and belief: lex orandi, lex credendi, or “the law of prayer is the law of belief.” This well-used axiom captures the idea that how the church prays is inseparable from what it believes. Theology is not developed in a vacuum but is shaped and reinforced through the regular practices of prayer and worship. Put simply, what the church prays, it ultimately believes, and what it believes must be faithfully reflected in its worship.

The language of worship is not incidental. As mentioned earlier, words form the very contours of Christian faith and practice. The repeated prayers, hymns, and creeds of the liturgy train the church’s spiritual imagination and inform the church’s understanding of God. Consequently, if worship is incoherent or theologically shallow, it does more than reflect doctrinal weakness — it actively cultivates and perpetuates it. N.T. Wright underscores this point in his book For All God’s Worth, observing that the way we worship directly impacts our understanding of who God is. Poor liturgy can distort divine truth, while robust, theologically grounded worship enables the church to know and love God rightly.

It is therefore essential that liturgy faithfully portray the character and nature of God. This conviction lies at the heart of the church’s historic commitment to creedal worship. The recitation of the Nicene Creed is not a mere intellectual exercise but a spiritual discipline, one that forms the faithful by engaging both heart and mind in worship. Through it, the church rehearses the truths of the gospel, nurtures theological clarity, and fosters a collective identity rooted in God’s self-revelation.

Within the context of Christian worship, therefore, the Nicene Creed occupies a vital role as both a theological anchor and a doxological witness. As an act of proclamation, it gives voice to the church’s shared confession and invites the gathered community to publicly affirm the core truths of the faith. As a liturgical act, it points to the redemptive work of God in history and anchors the present worship of the church in the eternal reality of the Triune God. As a doctrinal standard, it safeguards the church from theological drift, ensuring that its worship remains centered on the apostolic faith. In an age when worship can become overly emotive, individualistic, or culturally captive, the creed offers a necessary corrective. It prevents the church from slipping into self-referential spirituality by continually directing its gaze toward the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Similarly, because the reading and preaching of Scripture stand at the heart of Christian worship, the creed serves as a theological lens that guides and shapes faithful interpretation. Without such a framework, preaching risks becoming fragmented or driven by contemporary trends rather than rooted in the historic faith. The creed thus offers continuity and clarity amid the ever-shifting landscape of ecclesial discourse. Its enduring formulations resist distortion and novelty, keeping the church grounded in the apostolic message. In this way, the Nicene Creed is not only a statement of what the church believes but a guide for how it speaks and lives out that belief in the world.

The creed also protects against theological fads that may arise in different historical moments of the church. As new movements, ideologies, or interpretations emerge, the Nicene Creed remains a steadfast witness to the apostolic faith. As a safeguard, it prevents the church from being swayed by novel teachings that stray from the gospel. In this sense, the creed functions as both an anchor and a compass, keeping the church grounded in the core of the faith while guiding proclamation toward the eternal truths of God.

One further key liturgical strength of the creed is its role as a communal declaration of the church’s steadfast faith and allegiance to the Triune God. In a time marked by theological pluralism, denominational division, and doctrinal confusion, the Nicene Creed offers a unifying center. Despite differences in ecclesiology or sacramental theology, the creed is a common heritage embraced by Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant traditions alike. Its continued use across these diverse communities testifies to the enduring power of shared confession in binding the church together.

This unity is not superficial or abstract. It is grounded in a robust theological vision of the Triune God and the redemptive work of Christ. When the creed is confessed in worship, it transcends individual preferences and cultural differences, reminding the church that its foundation is not novelty or personal interpretation, but the unchanging truth of the gospel. Such unity is vital in an era when subjective experience often trumps theological fidelity. The Nicene Creed orients the church around truths that do not shift with the cultural tide.

Finally, the creed serves as a living act of worship that draws the church into the ongoing story of God’s saving work. It provides a theological grammar for the church’s worship and witness, rooting the gathered church’s praise and proclamation in the truths revealed through Scripture and affirmed by the historic church. Reciting the creed is thus both a formative and performative liturgical act: it not only communicates belief but actively shapes it, embedding the faith in the lived practices and participation of the community.

Notably, the creed is not something the church simply reads but something it prays. The act is a moment of participatory proclamation where believers collectively remember and re-enter God’s redemptive narrative. Lines such as “For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven” are not abstract propositions but confessions of praise, saturated with the drama of divine love. The creed thus becomes what Robert Webber describes as a way for the church to “do God’s story” in worship, mutually rehearsing the gospel narrative and inhabiting its truth with awe and gratitude. This act of remembrance is deeply formational, calling to mind the story of God’s redeeming love while drawing the church into deeper affection and trust.

Remembering is at the heart of worship. It is through remembering God’s saving work that the affections are stirred and faith is deepened. The words of the liturgy help us remember. The Nicene Creed, when regularly prayed and internalized, thus plays a crucial role in shaping the affections of worshipers. It cultivates reverence, love, and assurance, orienting the hearts of believers toward the living God.

By rehearsing the truths of the creed, worshipers are invited into the story of redemption. The confession of God as “Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth” evokes trust and wonder in the Creator’s providence. The proclamation of Jesus Christ, “true God from true God… who for us and for our salvation came down from heaven,” draws the congregation into the mystery of divine incarnation and the profound love it reveals. The affirmation of the Holy Spirit as “the Lord, the giver of life” reminds the church of God’s continual presence and work in the world.

The creed offers not only cognitive affirmation but also emotional stability. In moments of doubt, suffering, or confusion, it provides a constant reminder of the enduring truth and faithfulness of God. Its repetition embeds these truths in the heart, reinforcing the gospel’s power to comfort, sustain, and transform.

In this way, the creed nurtures rightly ordered love — orthodoxy (right belief) while fostering orthopathy (right affections). It reinforces that the purpose of right doctrine is not to win arguments but to love God more deeply and worship Him more fully.

Certainly, the Nicene Creed is far more than a theological relic or liturgical formality; it is a living confession that continues to shape the church’s identity, worship, and mission. It forms faithful Christians through repetition, anchoring doctrine in the liturgical life of the community, uniting believers across time and space, and stirring the affections toward deeper love and devotion. In praying the creed, the church not only remembers what it believes but becomes what it confesses: a people rooted in the truth of the gospel and oriented toward the glory of the Triune God. As the church continues to proclaim the words “We believe” in its worship, it does so as an act of ongoing formation — faith seeking understanding, worship expressing truth, and belief embodying love.

Jonathan A. Powers is the Associate Professor of Worship and Interim Dean of the School of Mission and Ministry at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky.

0 Comments