By Thomas Lambrecht —

A recent report by Lovett Weems of the Lewis Center for Church Leadership purports to examine the 2,000 or so churches that disaffiliated from The United Methodist Church by the end of 2022.

The Weems report was supposedly intended to discover the non-theological characteristics of these disaffiliating churches and how they are like or unlike the broader UM denomination as a whole.

After reading the report, one wonders if it was even necessary to have a prestigious team of researchers issue a blue-ribbon report that there are “more similarities than differences between the cohort of disaffiliating churches and the total pool of all United Methodist churches.” There is really nothing much to see here in the results of the analysis.

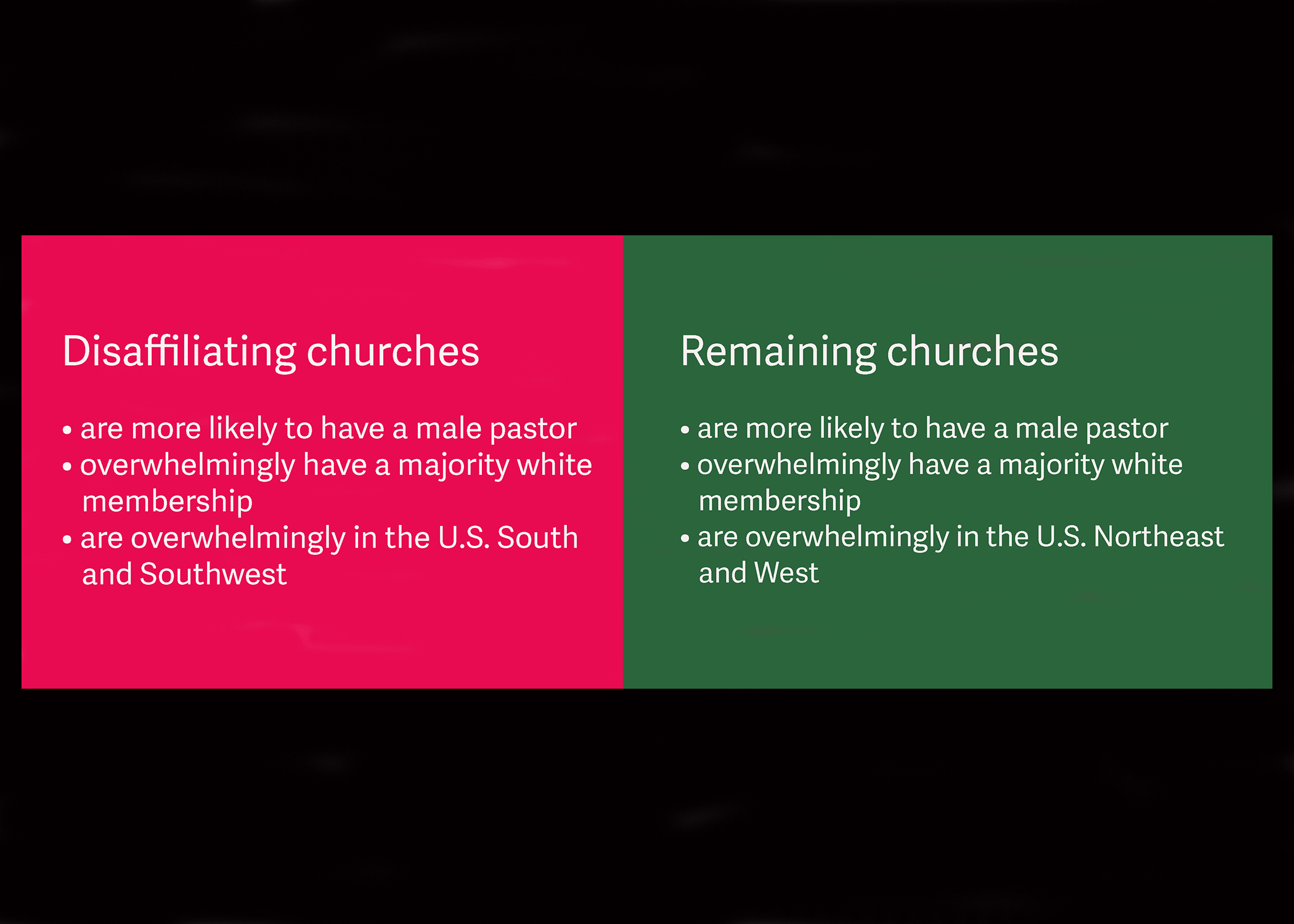

Nevertheless, in a fractious time where differences of opinion are characterized as “misinformation,” the report claimed: “But disaffiliating churches are overwhelmingly in the South with majority white memberships. They are also more likely to have a male pastor …”

The problem with issuing reports like Weems’ in a Twitter age is that statistics can make ham-fisted and non-insightful conclusions. The bullet point characterization shown at the top of this article is shallow and problematic. For example, one can look at the report and just as easily proclaim: Non-disaffiliating churches are overwhelmingly in the Northeast and West with majority white memberships. They are also more likely to have a male pastor.

Furthermore, someone can hardly be blamed for asking what exactly is the point of a study of a process that is only partially complete and does not have fixed variables for participants? Even The Lewis Center knows that all annual conferences are not treating the disaffiliation process evenly across the board.

Can someone be faulted for wondering if the fractured “analysis” was merely issued to paint disaffiliation as solely the interest of white, Southern, male clergy?

This is seen most prominently in Weems’ supposed three biggest takeaways. “The greater differences we found for disaffiliating churches compared to all churches came in the majority racial makeup of the congregation (white), location (Southern), and gender of the pastor (male).”

To fill out the picture, let us look more closely at what the Weems analysis shows and does not show.

A Preliminary Picture

The first thing that must be noted is that the data on which the analysis is based is skewed toward the early disaffiliators. About 2,000 churches had disaffiliated by the end of 2022, out of a total of about 30,500 United Methodist congregations. Thus, by the end of 2022, about 6.6 percent of all UM churches had disaffiliated. These disaffiliations took place over a 12-18 month period. That level of disaffiliation in such a short time is in itself extraordinary.

As noted earlier, each annual conference has a different disaffiliation process, and some annual conferences had an easier and/or more affordable process than others. Thus, the population of disaffiliating churches is not representative of what the whole population will be at the end of this process. Twenty-one annual conferences had fewer than 6 churches disaffiliate in 2022, including eight conferences that had zero disaffiliations.

Furthermore, there is still another year to run in the disaffiliation process before Par. 2553 expires at the end of 2023. Based on our contacts among annual conference leaders, the 2,000 churches that disaffiliated in 2022 represent less than half the total that will disaffiliate by the end of 2023.

In addition, if the 2024 General Conference provides a reasonable and just way for disaffiliation to continue, there will be more congregations leaving through the end of 2025. This will be particularly true if that continued pathway eliminates some of the egregious financial penalties being imposed by some annual conferences. Post-General Conference disaffiliation will increase if, as anticipated, the General Conference changes the definition of marriage, repeals the Traditional Plan, allows same-sex weddings, and welcomes non-celibate gay and lesbian clergy.

Weems’ analysis concedes, “It is anticipated that more will exercise this option [of disaffiliation] by the end of 2023 when the disaffiliation legislation expires. … It is impossible to know if further disaffiliations will mirror the characteristics of this first group of about 2,000 churches. There is a good chance that some patterns that are pronounced in their variation from overall United Methodist patterns may continue.”

The nature of the disaffiliation process as a disjointed, conference-by-conference process makes it less likely that the patterns of the early disaffiliators will persist in the final makeup of all disaffiliated churches in the end. One must take Weems’ conclusions with many grains of salt, pending a further analysis when we have come more nearly to the end of the process and have a more broadly representative sample.

Congregational Size

The first thing to note about disaffiliating churches is that they reflect fairly accurately the size categories of the general UM church. Weems found that “Compared to all United Methodist churches, disaffiliating churches are about the same mixture of churches by attendance size groupings.” The only real difference is that slightly more disaffiliating churches are between 25 and 50 in worship attendance, while slightly fewer are under 25 in worship attendance.

The story is floating around, spread by some UM leaders, that the disaffiliating churches are primarily small and rural. Weems found that is not the case. In our own analysis, at least 29 of the top 100 churches in worship attendance have disaffiliated or are known to be in the process of doing so. (There may be more.) Based on the overall percentage of churches disaffiliating (6.6 percent), one would expect only six or seven of the top 100 churches to disaffiliate. Four times the expected number have done so, meaning that the very largest churches are overrepresented in the population of disaffiliating congregations.

Location

Weems’ analysis makes a big point out of the fact that, so far, a greater percentage of disaffiliating churches are located in the South. Here are the percentages:

|

JURISDICTION |

PERCENT OF TOTAL UMC |

PERCENT OF CHURCHES DISAFFILIATING |

|

North Central Jurisdiction |

21% |

14% |

|

Northeastern Jurisdiction |

21% |

2% |

|

South Central Jurisdiction |

17% |

38% |

|

Southeastern Jurisdiction |

35% |

46% |

|

Western Jurisdiction |

5% |

1% |

It is important to understand the context of why this would be so. Many of the northern annual conferences did not have functional disaffiliation processes until this year. On the other hand, many of the southern annual conferences had much shorter and simpler disaffiliation processes that were in effect already in 2022. So the southern churches got a head start on the rest and are somewhat overrepresented in the total of disaffiliating churches.

The South Central Jurisdiction is by far the one that is most overrepresented among disaffiliating churches – 21 percentage points above its expected proportion. That is almost entirely due to three annual conferences in Texas. The Northwest Texas, Central Texas, and Texas annual conferences experienced a very high percentage of disaffiliations that took place relatively quickly in 2022. Texas had half its congregations disaffiliate, Central Texas a bit less than half, and Northwest Texas nearly three-fourths. These percentages are obviously much higher than the 6.6 percent across the denomination and skew the results toward the South Central. Once all the disaffiliations are completed in 2023, it is expected that the percent in the South Central will be closer to 22 percent, not far from the 17 percent that the jurisdiction makes up for the whole.

It is true that the Southeastern Jurisdiction includes a disproportionate share of traditionalist churches. That is not expected to change when the final results are in. Northern and Western jurisdictions have suffered a much greater membership loss over the last couple decades, and that has affected the number of remaining traditionalists in those areas. Traditionalists in the south have not seen their annual conferences affected by disobedience and liberal theology to the same extent, so there has been less motivation to leave the church. However, it is expected that the northern churches should nearly double their percentage of the total disaffiliated congregations in the end.

This whole discussion under location points out why Weems’ analysis is premature and subject to change as disaffiliations continue.

Growth and Decline

Weems found in his analysis that disaffiliating churches were more likely to have grown in attendance in 2019 (the year he used for comparison, which was pre-pandemic). He also noted that disaffiliating churches received fewer professions of faith compared to the denomination as a whole. Does that mean the disaffiliating churches emphasized attendance more than membership? Or would the increase in attendance show up as an increase in professions of faith in a future year? Or is membership growth coming more by transfer in those congregations? We do not know the “why” of these statistics.

It seems risky to classify a church as growing or declining based only on one year’s changes in statistics. Any number of factors can cause a blip up or down in the numbers in a given year, but do not represent the longer-term trend. It would be wiser to use a three-year or five-year growth pattern, but that would take a lot more time and effort to run those numbers for over 30,000 churches!

Racial and Ethnic Makeup

The Lewis Center research staff is well-aware of how sensitive the issue of race and ethnic makeup of a congregation can be. The United Methodist Church in the United States has historically been an overwhelming white denomination. We have justifiably worked for decades to make it more inclusive to reflect the broader American population.

Historically, United Methodism’s racial makeup is made even more complex because we have time-honored relationships with African American sister-denominations such as The African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ), and The Christian Methodist Episcopal Church (CME).

That is why it is not a special revelation that the Weems team found that an overwhelming majority of disaffiliating congregations were majority white from a denomination that is overwhelmingly white (in the United States). (Of course, the Global Methodist Church does have non-white leaders on its staff and Transitional Leadership Council and welcomes majority-non-white congregations.)

Other factors, such as the financial support that some ethnic churches receive from their annual conferences, as well as cultural dynamics, play into the decision of whether a given congregation will disaffiliate. When reading the report, it is also worth noting that many large Asian congregations on the West Coast and the Northeast are hampered by the requirement that they pay 50 percent of their (astronomical) property value in order to disaffiliate. Such a requirement makes disaffiliation financially impossible when they would owe millions or tens of millions of dollars.

So there are why racial and ethnic non-white congregations might think twice about disaffiliating.

Clergy Characteristics

Weems found that, “Compared to all United Methodist churches, disaffiliating churches have pastors who are less likely to be an active elder and more likely to be part-time local pastors, associate members, lay supply, and retired clergy.” Actually, Weems’ numbers show that pastors of disaffiliating churches are no more likely to be full-time local pastors, lay supply pastors, or associate members, compared with the denomination as a whole.

Disaffiliating churches were six percentage points less likely to be served by an ordained elder and three percentage points more likely to be served by a part-time local pastor or a retired pastor. Part-time and retired pastors are more likely to serve smaller congregations or congregations in transitional situations. Both full- and part-time local pastors are likely to be ordained as elders or deacons in the Global Methodist Church, meaning that GMC congregations will have a much higher percentage of their churches served by ordained clergy.

What struck me was the fact that only 43 percent of all UM churches are being served by an ordained elder. More UM congregations are served by full- or part-time local pastors or supply pastors. Yet the UM system is designed to serve mainly elders. Local pastors and supply pastors have no guarantee of a job and are at the mercy of the bishop and district committee on ministry. It is amazing to me that as many churches with local or supply pastors decided to disaffiliate as have done so. Perhaps one reason is that such pastors will have far more power and support in the GMC.

Weems also determined that, “Compared to all United Methodist churches, disaffiliating churches have pastors who are more likely to be male. Only 17 percent of disaffiliating churches have a woman as lead pastor compared to 29 percent for United Methodist churches as a whole.”

However, the numbers behind this conclusion are questionable. Apparently, the data used for Weems’ analysis does not include a designation of gender for the pastor. Weems and his team went through 30,000 clergy name by name and assigned the probable gender based on their name. I can only imagine the monumental workload this process took! It is a subjective judgment for each name whether it is male or female. The margin for error must be high. In addition, Weems has stipulated in email correspondence that they could not identify the gender for 3 percent of UM pastors and 5 percent of disaffiliating church pastors.

Because of these questions, it is dubious whether the “gender gap” is as wide as Weems suggests.

On the other hand, it would not be surprising that there would be somewhat of a “gender gap” among pastors in disaffiliating churches. I have spoken to numerous female pastors who have traditional theology and are therefore ostracized in their annual conferences because of it. If traditional-minded female pastors find United Methodism inhospitable, they would not likely stick around very long in the ministry or perhaps not even get admitted in the first place.

Conclusion

Mark Twain quoted the British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli as saying, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Statistics can sometimes be made to tell a false story or support a weak argument.

Weems’ analysis should be regarded only as a preliminary snapshot – an inadequate one at that – of disaffiliating churches at the end of 2022. The situation can and will change before all the dust has settled. The context around numbers can help us bring the picture into better focus. Most importantly, the numbers themselves do not explain “why” the picture is the way it is. For that, we will need to dig deeper over the years ahead. In the meantime, Weems’ analysis should not be made to tell a story that the numbers do not really support.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News.

It seems like Traditionalists are like Moses telling Pharaoh (UMC), “Let My People Go!” As Rev. Carolyn Moore thoughtfully said, “Unity at all costs is not unity at all”; “There is a tendency in the church to minimize the differences rather than honoring the differences” and “healing is not going to happen without space”. We as traditionalists need to be separated from those who “hate” us because the caustic environment is not healthy for anyone.