An Anglican Reflection on the Nicene Creed for Fellow Wesleyans —

By W. Brian Shelton –

Among the many types of Wesleyans who commemorate the 1700th anniversary of Nicaea this year, those in the Anglican Church may be easy to overlook. The emergence of Methodism within the eighteenth-century Church of England led to a swelling of its ranks and a separation from its original church. However, their common roots meant that these two branches would share theological similarities and ensured that they could always be closely connected.

Methodism was a renewal movement within Anglicanism, bringing a new energy centered on personal repentance, salvation, and sanctification to the established church. As a Methodist in my youth and my middle age, I now find myself Anglican, having here experienced a form of personal renewal that reverberates with the energy of the eighteenth century. Central to this experience has been worship steeped in theology, including the Nicene Creed. While it is not surprising that a theology professor at worship would appreciate this quality, the creed offers a theological experience that can remind Wesleyans everywhere of our core beliefs, such as the Trinity, incarnation, salvation, church, and an eternal hope. These common beliefs orient us, inspire us, and unite us, and when they are appropriated to the heart, they can renew us. As a Wesleyan in the Anglican Church of North America, an Anglican appreciation of the Nicene Creed in the life of the church is offered here.

Article 8 of the Thirty-Nine Articles states that the Nicene Creed is one of three creeds that “ought thoroughly to be received and believed: for they may be proved by most certain warrants of Holy Scripture.” The phrase “received and believed” embodies how all Christians treat this ancient creed — accepting it from a historic church (received) and professing it for our generation (believed). This very act of saying the creed together is akin to the Wesleys’ vision to practice faith in community. Before striking out into good works, we begin with this foundation for belief that motivates and justifies our own spiritual formation, as well as the ministries to one another and to the world. Three reasons strike me for why an Anglican view of the Nicene Creed has been valuable to me and can be to Wesleyans everywhere.

First, it is said. I have been a member of Methodist churches that say no creed. My own formative years as a teenage Christian saw me thrive spiritually without any creedal element. I have been a member of one Methodist church that regularly said the Apostles Creed. This habit grew on me as a congregational member, as I joined fellow-believers in worship to confess what we all believed. However, the Nicene Creed is rare in Methodist circles. Now, I am a member of an Anglican Church that faithfully says this confession every Sunday. Like saying other parts of the liturgy with regularity, such as the Lord’s Prayer and “the peace of Christ to you,” one can become immune to its significance by uttering the same words, time after time. However, for the one who thinks on the words, internalizes them and lifts them up in a confession of praise, the Nicene Creed remains powerfully inspirational. By stating out loud, “I believe” in the person and work of God, one joins a profession of believers throughout time that uttered this same profession. By stating out loud, “I believe” in the qualities and accomplishments of God, one gets refamiliarized and reoriented to the One we worship. We can become amazed when spoken words make a claim about something more wonderful and epic than ourselves.

Second, it is profound. The words of the Nicene Creed describe the nature of God and the work, summarizing the narrative of the biblical story that makes application across all sectors of worship practices. It tells of the Father creating “all things visible and invisible.” It tells of the Son being sent by the Father, “God from God.” It tells of the purpose of this wonderful work for sinners, “For us and for our salvation, he came down to earth.” It tells of “the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of life,” reminding us of our created status and our reliance on the Creator for life itself. Finally, it tells of our place on this great timeline, participating in “one holy, catholic and apostolic church,” a place in which we “look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.” The Nicene Creed captures the dynamics of the Trinity who delivered for us the promise of a new life. It offers an intellectual dimension that accompanies the affectual experience so common to contemporary evangelical churches. In saying the creed, one is confronted with the profound story of a limitless God who accepted limits to free a sinful people from their limits—those very people saying the creed. The profundity of this reality is almost too hard to believe.

Third, it is renewing. This element may be the most surprising, as the same words are professed in Anglican churches week after week until they engrain habitually into the mind. In fact, the same words have been professed, over and over, leading up to the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea this year. Just as the wonder of God continues to bless us in life, the profound reality of the creedal words continues to inspire us to realize and hope for such blessings. The creed holds a promise that the God of the bible, with all the miracle stories, all the stories of changed lives, and all the stories of hope are available to us. A reminder of that biblical promise gets delivered in the saying of the Nicene Creed, where we recite words that can be renewing to us. This is no truer than in the prayers of the people in the Anglican service: “For the peace of the world, for the welfare of the Holy Church of God, and for the unity of all peoples, let us pray to the Lord.” The God of the Nicene Creed can unite his people in common belief, renewing them individually even as they say together, “I believe in one…Church.” After all, spiritual renewal is an important component of worshipping on the Lord’s day.

An Anglican perspective on the Nicene Creed offers still more. This confession is a boundary to human teaching. It is no surprise that in our worship service, the Nicene Creed and the reading of scripture surround the homily. The scripture and its creed bracket the sermon—the only part of the worship service that risks being humanly manufactured. This confession is also a contemporary profession of faith, stated in the present but also grounded in a historical reality. It offers a connection to the past, reorienting our generationally-centered “us” and “now” to a historic participation with believers who went before us. In turn, this invites us to join something bigger than just our church in our present lives. This confession also invites all to believe its contents, welcoming a diversity of denominations without allowing any diversity of unorthodox beliefs to corrode its foundation. This confession thus allows Wesleyans to find a synthesis with their own distinctives on universal salvation, the pursuit of holy living, and a focus on community service in a context of a deeper, precise, and historic Christianity.

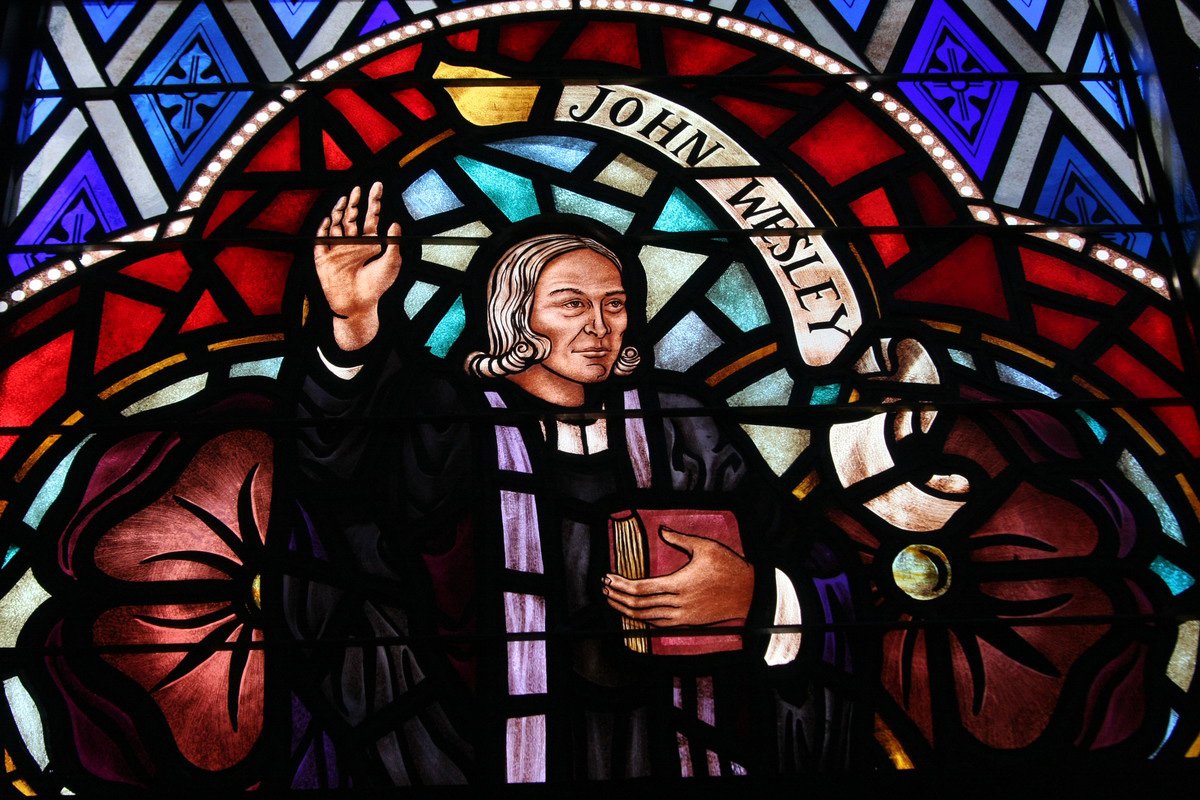

However, all this optimism around an Anglican appreciation for the Nicene Creed along Wesleyan lines does not come without two concessions. First, in guiding American Methodists along the Anglican-Methodist way, John Wesley omitted Article 8 of Thirty-Nine Articles cited above and he removed the Nicene Creed in his condensed service for communion. Scholars often speak of his unsystematic writings and his propensity for a lived faith. In Methodists in Dialog, Geoffrey Wainwright describes how Wesley had “no quarrel with the substance of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed” (191) and that orthodox doctrine was “not so much unnecessary as insufficient — if it was not believed, experienced, and lived” (195). Second, saying the creed weekly can take some conditioning for Wesleyans who may not be used to consistent liturgical patterns of worship. Appreciating both its contents and the power of a united confessions can require some exposure. As Anglicans live in such a worship culture, that conditioning is developed to appreciate the value of the Nicene Creed in worship.

With such a confessional commitment comes a chance for personal and corporate renewal. Perhaps one of the best ways to discover and anchor a renewal movement like Methodism — whether in the eighteenth century or as its renewal is underway these days — is in the profession of the Nicene Creed. After all, the God worshipped there is the one who enables us to live as “one, holy” church of God, renewed by “the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life.”

W. Brian Shelton, PhD is Dean of the School of Christian Studies, Professor of Theology, and Wesley Scholar in Residence at Asbury University in Wilmore, Kentucky.

0 Comments