by Good News | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

“John Wesley represents an intriguing synthesis of old and new,” wrote Howard Snyder in Radical Wesley, “conservative and radical, tradition and innovation that can spark greater clarity in today’s new quest to be radically Christian.” Photo: Shutterstock.

By Winfield Bevins –

It’s easy for contemporary Christians to think that John Wesley, the great revivalist and leader of the Great Awakening, was opposed to church tradition altogether. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, he was a high churchman who loved church tradition, the sacraments, and the Anglican liturgy. He used the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, which contains orders of services, ancient creeds, communal prayers, and a lectionary. Wesley said, “I believe there is no Liturgy in the world, either in ancient or modern language, which breathes more of a solid, scriptural, rational piety than the Common Prayer of the Church of England.”

While at Oxford, Wesley and his brother Charles were accused of being “sacramentalists” because of their insistence upon taking communion regularly. It is said that Wesley took the Lord’s Supper at least once every four to five days, and he encouraged the Methodists to celebrate the Lord’s Supper weekly. Wesley said, “It is the duty of every Christian to receive the Lord’s Supper as often as he can” (“The Duty of Constant Communion”). These are hardly the words of a non-traditionalist.

In many ways, early Methodism could be described as a movement that was founded on tradition and innovation. Wesley traced the Methodist genealogy back to the “old religion,” describing Methodism as “the old religion, the religion of the Bible, the religion of the primitive Church, the religion of the Church of England.” For Wesley, Methodism was not something new, but another link in an unbroken chain of true religion, a religion of the heart, which was “no other than love, the love of God and of all mankind” (“On Laying the Foundation”).

“Wesley’s ecclesiology was a working synthesis of old and new, tradition and innovation…True renewal in the church always weds new insights, ideas, and methods with the best elements of history,” writes Howard Snyder in Radical Wesley. “And true renewal is always a return, at the most basic level, to the image of the church as presented in Scripture and as lived out in a varying mosaic of faithfulness and unfaithfulness down through history. John Wesley represents an intriguing synthesis of old and new, conservative and radical, tradition and innovation that can spark greater clarity in today’s new quest to be radically Christian.”

This return to a more primitive form and practice of Christianity primarily meant returning to the spiritual vitality that was characteristic of the book of Acts and the early church. Wesley and the early Methodists had a vision to recapture a “contagious faith” and to spread it around the world: “Scriptural Christianity, as beginning to exist in individuals; as spreading from one to another; as covering the earth” (“Scriptural Christianity”).

It clearly states on Wesley’s tombstone, that the heart of the Wesleyan revival was the rediscovery of “the pure apostolic doctrines and practices of the early church.” But Wesley did more than read and study the past. He took what he learned and reapplied it, contextualizing it to his own time and place. More than that, he used what he learned to create a disciple-making movement that equipped and empowered thousands of people to join in God’s mission.

The Tension of Tradition and Innovation. One of the secrets of the success of Wesley’s movement was his ability to maintain a dynamic synthesis of old and new, tradition and innovation. While he wasn’t against tradition, Wesley was opposed to dead, dry religion, cold ritualism, and the clericalism that discouraged non-ordained people from being involved in the life of the ministry, all of which had become widespread in the Church of England in the eighteenth century.

The Wesleyan synthesis could perhaps best be viewed as a tension between the embrace of tradition and the need for innovation. While Wesley was a traditional high church Anglican priest who honored church tradition, at the same time, he was an apostolic leader who was willing to innovate, willing to bring change to the structure and methods of the church in order to see the gospel shared and lives changed.

While Wesley honored this tradition, he was not bound by it. He was far more concerned with saving souls, and he believed that the Lord was doing an extraordinary thing by raising up the Methodists and calling non-ordained men and women to preach and serve as leaders in the church. This, perhaps more than anything else, was why Wesley faced such opposition to his work. His embrace of non-ordained people to preach and lead bypassed the institutional hierarchy and upset the status quo. His empowerment of an army of non-ordained women and men was nothing short of revolutionary at a time when the church relied almost solely on clergy to accomplish Christ’s mission.

Wesley worked to keep the old and the new in tension. He began to envision two kinds of ministerial orders: the ordinary Anglican clergy and the extraordinary Methodist preachers. Wesley saw a role for Anglican ministers in providing pastoral oversight of a congregation and administering the sacraments, while the purpose of the extraordinary Methodist preachers was preaching and evangelizing the lost.

Wesley used the Scriptures to aid him in embracing the tension he held between tradition and innovation, between the old and the new. He continued to believe in the need for the ordinary and established Anglican clergy, but he believed that there was an equally significant role for the non-ordained preachers and workers of the Methodist movement. The church was filled with ordained clergy, yet it was not meeting the need of the world to hear the gospel message.

What was needed was an army of lay preachers and evangelists who would preach the good news at every highway and in the hedges. To this vision, Wesley was willing to give his life, dedicating his time and energy to empower a new and extraordinary order of ministry. The result of Wesley’s embrace of tradition and innovation was the birth of one of the greatest Christian movements the world has ever known.

Tradition and Innovation Today. Wesley reminds us that we need tradition and innovation to face the challenges and complexities of today’s world. We do not need innovation at the expense of tradition. Rather, we need innovation that is rooted in tradition. I believe the future mission of the church will be found on the road where the past and the present meet in a re-traditioning that embraces the best of tradition for the sake of the future through tradition and innovation.

The combination of tradition and innovation does not mean compromising time-honored essentials of orthodoxy or church tradition, but rather bringing those essentials into dialogue with the present realities of the church in a beautiful convergence of old and new. I believe the church of the future will need to be rooted in Scripture, tradition, liturgy, and sacraments, while at the same time fully engage in mission at the intersection of the gospel and culture.

By using the term “tradition,” I do not mean tradition with a capital T, as in Roman Catholicism or Lutheranism, but rather I am referring to tradition with a lowercase t, as in what has been common to all Christians in all ages, especially during the first five centuries of the church.

Maybe you’re thinking to yourself, “Isn’t tradition just dead religion?” We need to distinguish between tradition and traditionalism.

Historian Jaroslav Pelikan describes the difference between tradition and traditionalism. “Tradition is the living faith of the dead; traditionalism is the dead faith of the living,” he said. “Tradition lives in conversation with the past, while remembering where we are and when we are and that it is we who have to decide. Traditionalism supposes that nothing should ever be done for the first time, so all that is needed to solve any problem is to arrive at the supposedly unanimous testimony of this homogenized tradition.”

With Wesley, I believe the church of the future will be one that is rooted in tradition and innovation. The recovery of tradition doesn’t mean that we should try to relive the past; it’s about retrieving it and appropriating it into the context of life in twenty-first century North America. I am not advocating reverting back to “the good ol’ days,” but proposing a way for the past, present, and future to come together for a new generation that is rooted in tradition and innovation. I believe that the future of the church not only lies in the traditions of the past, but in the unique implementation of these concepts in our world today.

In his book You Are What You Love, James K.A. Smith calls this integration “tradition for innovation.” He reminds us that tradition should be seen as a resource to foster cultural innovation because it provides us with rich imaginative practices that are rooted in historic Christian worship. Here are some of Smith’s examples of how liturgy fosters a fresh missional imagination:

“Kneeling in confession and voicing ‘the things we have done and the things we have left undone …’ tangibly and viscerally impresses upon us the brokenness of our world and humbles our own pretensions;

“Pledging allegiance in the Creed is a political act – a reminder that we are citizens of a coming kingdom, curtailing our temptation to over identify with any configuration of the earthly city;

“The rite of baptism, where the congregation vows to help raise a child alongside the parents, is just the liturgical formation we need to be a people who can support those raising children with intellectual disabilities or other special needs;

“Sitting at the Lord’s Table with the risen King, where all are invited to eat, is a tactile reminder of the just, abundant world that God longs for.”

I believe this is one of great needs in the world today: holding tradition and innovation, old and new, together in a dynamic way. The recovery of tradition and innovation was at the heart of the Wesleyan revival. Wesley wanted to recover the old religion and connect his generation with the early church and its teachings, but Methodism was also something new, contextualized for his time and place, and Wesley was able to give old truth fresh expression. When he spoke about recovering “Scriptural Christianity,” Wesley meant a return to the pure, undefiled “religion of the Bible, the religion of the primitive church” (“On Laying the Foundations.”)

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.

Winfield Bevins the Director of Church Planting at Asbury Theological Seminary. He also is a frequent conference speaker and author. Some of his recent books include Ever Ancient, Ever New: The Allure of Liturgy for a New Generation and Marks of a Movement: What the Church Today Can Learn from the Wesleyan Revival. This essay originally appeared on Firebrand (firebrandmag.com) and is reprinted by permission.

by Good News | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

Mosaic of Father Damien in the Maria Lanakila Catholic Church in Lahaina, Hawaii, established in 1846. Father Damien, who had worshiped there, gave his life to the lepers on Molokai. Photo by Steve Beard.

By Steve Beard –

Looking across the shades of aqua blue water from the northwest coast of Maui, there are two Hawaiian islands seen in the distance. One is Lanai, once home to the largest pineapple plantation in the world. Today, the island is privately owned by billionaire Larry Ellison of Oracle and known for its exclusivity, luxurious accommodations, and spectacular golf course.

The other island is Molokai, known around the world for over a century because of the selfless ministry of Father Damien. From the first time I saw the two sparsely populated islands, Molokai’s tragic and triumphant saga of faith and kindness has held a magnetic appeal.

In 1866, the Kingdom of Hawaii forcibly exiled those suspected of having leprosy (known today as Hansen’s disease) to a small plot of land on Molokai. Called Kalaupapa, the peninsula is surrounded on three sides by the majestic Pacific Ocean and boxed in by a towering 3,600-foot cliff. Father Damien called it a “living graveyard.”

At age 33, Damien unhesitatingly volunteered to be a priest to the rejected and dejected in exile. Ten years previous, he left his native Belgium and spent five months at sea to become a missionary to Hawaii. He was a pious, head-strong, and resourceful priest. To his superiors and fellow priests, going to Molokai was a death wish. Furthermore, the colony had the lawless deterioration of the Lord of the Flies.

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here” reads the sign above hell in the 14th century poem describing the afterlife in Dante’s Inferno. It also could have been written at the unforgiving shoreline of Molokai for those who had been rounded up and sentenced to a lifetime of misery away from friends, ohana (family), and civilization. When the bishop escorted Damien to the island, he introduced the priest to the 800 exiles as one “who loves you so much that he does not hesitate to become one of you, to live and die with you.” No truer introduction could have been pronounced.

Father Damien was a spiritual first responder. Squalor, pain, and suffering surrounded him. And the smell was putrid. “Many a time in fulfilling my priestly duties at their domiciles I have been obliged, not only to close my nostrils, but to remain outside to breathe fresh air,” he confessed. “As an antidote to counteract the bad smell I got myself accustomed to the use of tobacco.” The aroma of his pipe gave him some relief.

“Picture to yourself a collection of huts with 800 lepers,” he wrote to his brother. “No doctor; in fact, as there is no cure, there seems no place for a doctor’s skill.” What he witnessed and experienced was overwhelming. Despite the horrific circumstances, Damien ate from the same bowl as the afflicted, used his fingers to feed poi to those with no hands, shared his pipe, embraced the ill, and gave last rites to the dying. Although he had been sternly warned against physically touching those of his flock, he did the opposite.

Bodily disfigurement came with the disease. Yet, Damien knew that “they also have a soul redeemed at the price of the precious blood of our Divine Savior,” he once wrote. “He too in his divine love consoled lepers. If I cannot heal them, as he could, at least I can offer them comfort.” With gumption and compassion, he even tried to read medical books to help alleviate pain and suffering. He cleaned and bandaged the ghastly wounds, and was even forced to learn to amputate limbs.

In his acts of mercy, Damien expressed his belief that Christ is present in all our sufferings. He worked tirelessly so that those who had been abandoned knew that God, too, did not turn his back. He looked at the innocent orphans and was confident that they had done nothing to deserve leprosy – countering a prevailing belief among some at the time that it was a divine punishment.

As he held the dying, he demonstrated through his embrace: You have dignity. You have worth. You have intrinsic value.

“With parishioners like his Hawaiians, touch was all-important. With a priest like Damien, in whom belief was unaffectedly incarnate, faith was made physical,” writes historian Gavan Daws in the biography Holy Man (University of Hawaii Press). “To mortify the body, to die to himself, to risk physical leprosy in order to cure moral leprosy – this was to be a good priest. If it meant touching the untouchable, then that was what had to be done. The touch of the priest was the indispensable connection between parishioner and church, sinner and salvation.”

From the outset, he addressed his flock: “We lepers.” Damien faithfully preached, baptized, heard confessions, built caskets (an estimated 1,000), dug graves, and buried the dead with respect. He lived the virtues of aloha to those who had been sequestered to die. Furthermore, without timidity, he hounded the government and religious leaders – much to their irritation – for medical supplies, clothing, food, lumber, and piping to provide fresh water to the colony. He was a tireless advocate for the ostracized and forgotten. “I find my greatest happiness in serving the Lord in his poor and sick children – who are rejected by others,” he wrote.

Despair was an ever-constant and dark storm cloud over Molokai. How could it not be? In addition to his priestly duties and doing everything he could to improve living conditions – including building shelters and blasting rocks to create a dock – he also tried to bring joy and purpose to those who were sent there simply to die. Damien organized choirs, an orchestra, horse races, and baseball games.

In his journal, he reminds himself: “Be severe towards yourself, indulgent toward others. Have scrupulous exactitude for everything regarding God … Remember your three vows by which you are dead to the things of the world. … Remember that God is eternal and work courageously to one day be united with him forever.”

As to be expected, even saints become agitated, depressed, and lonely. Father Damien was no exception. Death was omnipresent. “The only thing that really grows here is the cemetery,” he once wrote. “The pews in the church are somewhat emptier, while in the cemetery there is hardly room left to dig the graves.”

At age 49 – after 13 years on Molokai – he discovered that he had contracted the dreaded disease. By this time, despite a handful of detractors and critics, Father Damien had effectively raised awareness around the globe about the plight of those who suffered from Hansen’s disease. His selfless work found support from warmhearted people of all nationalities, politics, and creeds. Princess Liliuokalani presented Father Damien with a medal as a Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalakaua – the highest honor of the royal family in Hawaii.

“I am gently going to my grave,” he wrote shortly before his death, three years after contracting the disease. “It is the will of God, and I thank him very much for letting me die of the same disease and in the same way as my lepers. I am very satisfied and very happy.” He died during Holy Week in 1889. For Father Damien, Easter was celebrated in eternity.

In 1936, when there was word that the humble priest was being considered for sainthood, King Leopold III contacted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to get assistance in exhuming the body of Father Damien from Molokai (then the U.S. Territory of Hawaii) and returning it to his native Belgium. The Hawaiians who knew his complex personality – and saw firsthand the fruit of his energetic and industrious ministry – were devastated.

Decades later, in a much-appreciated move, Pope John Paul II saw to it that the remains of Father Damien’s right hand were returned to his original gravesite on Molokai. It was a fitting tribute to the saint who purposefully held out his hand to the untouchable.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Good News | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

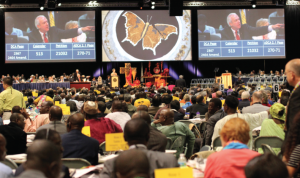

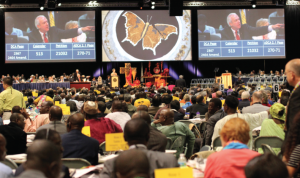

Proceedings of the 2012 General Conference of the United Methodist Church in Tampa, Florida. Photo by Steve Beard.

By Joseph F. DiPaolo –

There’s been lots of speculation about the upcoming General Conference of The United Methodist Church – when it will happen, whether it will happen, what the delegates are likely to do, and what they should do.

This is not surprising. Since 1968 (indeed, since 1792), General Conference is where the buck has always stopped.

Until recently, that is. A big reason we are on the verge of division is because, for the first time since 1792, some folks and groups within the church (including some bishops and even whole annual conferences) have decided that the decisions and policies of General Conference can be ignored or defied. Still, when it comes to legal issues around property, pensions, and liabilities, General Conference has the final word.

But there are even more important reasons why General Conference must meet and soon: to act on the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation and end the state of limbo we are all enduring.

For one thing, only General Conference speaks for the whole church. Many voices today are making predictions and pronouncements about the state of the UM Church, about what annual conferences can and cannot do, about what would be just and fair in any division of the church. The problem is that only General Conference – not any bishop, agency executive, or clergy blogger – speaks for the whole church. Only General Conference brings together representatives from every conference across the globe to decide on questions which affect the whole denomination. It is a messy process, to be sure, but the only one which truly gives voice and vote to all the constituent parts of the body.

In addition, only General Conference can create a consistent policy for the whole connection. Did you know that annual conferences have always been able to allow congregations to leave with their property? Even before the disaffiliation clause was added to the Discipline in 2019, annual conferences sometimes suspended the trust clause when a church closed, merged or federated, or simply negotiated to become independent. As a result, individual annual conferences could, if they chose, create their own versions of the Protocol. But this would be a very uneven and uncertain process across the denomination, and likely create inequities depending on the specific culture and leadership of individual conferences. Only General Conference can create a just and fair process that encompasses the whole denomination.

Finally, only General Conference can prevent the church from devolving into bitter conflict and expensive legal battles over property. The bitter polarization of North American culture has infected the culture of the church, and we have seen it play out at annual, jurisdictional, and general conferences. It has not been pretty. But we now have an opportunity to model a different way, even amid our own deep divisions.

Instead of continuing to fight and trying to force each other into complying with our side’s agenda, progressives and traditionalists can choose to bless one another to pursue different visions of ministry in separate institutions. If we cannot agree on “what Jesus would do,” can we at least agree “what Jesus would not do”? – and surely Jesus would not resort to the power of government (enforcing the trust clause) to make people follow and support him. We can choose to minimize the pain and harm of dividing by agreeing to do so amicably and fairly. We can choose to be guided by principles of graciousness, respect, and the golden rule, and preserve some measure of goodwill to allow for post-separation cooperation on areas of common concern.

For those things to happen, we need the General Conference to meet, and to act on the Protocol.

As a member of the Commission on General Conference, I can tell you that we are still working and planning with the expectation that the deferred 2020 General Conference will meet, as announced, next August. Of course, no one knows what international crisis may erupt, or how the ongoing pandemic will evolve – who could have predicted the last year and a half? Both the Commission members and the Commission staff are acutely aware of the importance of having the General Conference meet and getting the church “unstuck” as soon as possible. I can attest to the professionalism and competence of the General Conference staff, which is constantly exploring ways to make General Conference happen. And I can testify that, even with the differences of opinion and theology represented on the Commission, all have worked well together to do our job, which we know is limited to planning and organizing the gathering; it is up to the delegates to deliberate and decide on the issues and policies.

I am hopeful! Many organizations have found ways to “pivot” and adapt these last 18 months in order to conduct business – including a sibling, global denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which successfully convened a hybrid General Conference this past July. More things are possible today than just six or eight months ago. And of course, all things are possible with God!

I am hopeful! Many organizations have found ways to “pivot” and adapt these last 18 months in order to conduct business – including a sibling, global denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which successfully convened a hybrid General Conference this past July. More things are possible today than just six or eight months ago. And of course, all things are possible with God!

Pray for wisdom and discernment for the members and staff of the Commission. Pray that the Lord will soon deliver us from this global plague. And pray that the General Conference will soon meet to resolve the current impasse, adopt the Protocol, and enable a new day to dawn for those of us who follow Christ in the Wesleyan way.

The Rev. Joseph F. DiPaolo is lead pastor at Lancaster First United Methodist Church in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He is a member of the Wesleyan Covenant Association Global Council and also serves as a member of the UM Church’s Commission on the General Conference. This aricle is reprinted by permission of the Wesleyan Covenant Association.

by Good News | Dec 22, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

The Rev. Rob Renfroe, president of Good News

I do not believe you will find a book in the Bible more relevant to The United Methodist Church than the Epistle of Jude.

Early in his letter Jude writes: “Although I was very eager to write to you about the salvation we share, I felt compelled to write and urge you to contend for the faith that was once for all entrusted to God’s holy people. For certain individuals have secretly slipped in among you. They are ungodly people, who pervert the grace of our God into a license for immorality and deny Jesus Christ our only Sovereign and Lord” (verses 3-4).

Jude tells his readers he had intended to send them a letter going into depth about our salvation in Christ. But grave reports about matters in the church have compelled him to write a very different letter. The problem? False teachers in the church are denying Christ and promoting immorality.

What are the characteristics of those leading the church astray?

1. They claimed a wrong source of authority. “Yet in the same way these dreamers also defile the flesh, reject authority, and slander celestial beings” (verse 8, emphasis added). What is the basis for their heretical teaching? Their dreams. Their visions. Their personal experiences that tell them we should embrace a truth that is contrary to what Jesus and the apostles taught.

The false teachers Jude described are similar to false teachers and prophets throughout the ages. They say, “God has told me.” Or “the Holy Spirit has revealed something to me.” What they claim to be their personal revelation now trumps what the Scriptures teach.

In our time the phrase is usually, “The Holy Spirit is doing something new.” And false teachers claim to be privy to this revelation in a way the rest of the church is not. No matter that the Scriptures are clear, and the church has taught the same doctrine for 2000 years, and 95 percent of all Christians around the globe still uphold what the church has taught for millennia. A relatively few, “enlightened” Western Christians in a hedonistic, postmodern culture now believe they alone have been chosen to receive and promote a novel doctrine that supersedes what the Scriptures reveal to be God’s will.

Ask them how they know this is God’s revelation and they have a difficult time responding. They just know it. They feel it. It’s obvious, in their minds, that God is doing a new thing that is pleasing to our culture and anathema to the Bible.

I once asked a respected progressive pastor how he could promote what was contrary to the Bible. He was very frank. He told me, “Rob, the church created the Bible. So, we can re-create the Bible.”

And on what basis? Our feelings, our imaginings, our dreams? A belief that this is what all “good, loving people” would teach as the truth if they were God? For those who taught false doctrines in Jude’s day and for false teachers in our own time, yes, a foundation as flimsy as an individualistic conviction that the Bible cannot be right is sufficient to claim that God is revealing new truth.

2. They possessed a wrong Christology. Past cults have taught that Jesus was not truly divine – they esteem him as a moral teacher, a cultural reformer, or a highly-evolved being who realized his God-consciousness. But they do not believe he was God incarnate.

What does Jude say about the false teachers of his time? “(They) deny Jesus Christ our only Sovereign and Lord” (Jude 4). How exactly they were doing this, we are not told. But in some way, they were diminishing the uniqueness and the Lordship of Jesus. They were making him one of many rather than the One and Only.

Today, what you may hear is “Jesus is my Savior and my way, but there are many ways – all of them valid.” I once asked a UM pastor who was a candidate for bishop if other religious teachers, Buddha and Mohammad, for example, brought the same kind of revelation and truth to their followers that Jesus brings to Christians. Quickly and unashamedly, he responded, “Oh, yes. I tell my students, ‘God is wholesale. Jesus is retail.’” Buddha, Mohammad and Jesus are simply retail outlets for the same wholesale God – just different ways of receiving the same (saving?) truth.

By the way, who were his students? Men and women training to become pastors at the United Methodist seminary where he taught.

A related way the divinity and uniqueness of Jesus is diminished is through implied universalism. This is the belief that everyone will go to heaven and that there is really no need for people to surrender their lives to Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord. The lack of urgency around evangelism in our denomination betrays the unspoken understanding of many that faith in Christ is a good thing for those who want it, but it is not necessary for salvation and eternal life.

I wish I could tell you these understandings of Jesus are uncommon within the UM Church. But the truth is this false teaching has been propagated in our seminaries for decades and it has infected many of those who are now serving as our pastors and preaching in our pulpits.

3. They promote a wrong understanding of morality. They pervert the “grace of our God into a license for immorality” (Jude 4). Wrong beliefs will lead to wrong behavior. Deny the authority of the Scriptures and the full divinity of Christ, and you can be sure that a compromised morality will soon follow.

Throughout the ages, there have been three responses to God’s grace. One is legalism – those who sin cannot remain in fellowship with the body of Christ. Another is license (what the false teachers in Jude’s letter were and many in our own time are embracing) – because of grace we are free to live as we desire. God will accept us and affirm whatever behavior we believe is right for us. The third response is liberty – through the work of the Spirit, we become free from the power of sin and begin to live a new life.

True freedom is not the right or the ability to do whatever we desire. True freedom is the power to do whatever we should, including dying to the base desires of the flesh and living a life that pleases God.

Jude told his readers and I tell you: The truth is under siege. It’s being undermined by some in the church. By teachers in the church. And the charge for us is the same that Jude gave to his readers “Contend for the faith once and for all entrusted to the saints” (Jude 3).

The United Methodist Church is divided on the most basic beliefs any church can face. Do we follow the Scriptures? Do we confess Jesus as Savior and Lord, the only begotten Son of God? Do we believe grace leads to license or liberty?

We orthodox Wesleyan Methodists are to know the truth; promote the truth; and, where it is under attack, contend for the truth. For it is the truth that will set us free.

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.

I am hopeful! Many organizations have found ways to “pivot” and adapt these last 18 months in order to conduct business – including a sibling, global denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which successfully convened a hybrid General Conference this past July. More things are possible today than just six or eight months ago. And of course, all things are possible with God!

I am hopeful! Many organizations have found ways to “pivot” and adapt these last 18 months in order to conduct business – including a sibling, global denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which successfully convened a hybrid General Conference this past July. More things are possible today than just six or eight months ago. And of course, all things are possible with God!