by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Archive: Coming Out of Exile

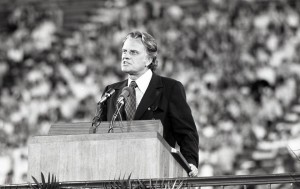

Photo courtesy of Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. All rights reserved. www.billygraham.org.

By Riley Case-

The 1960s were not a good time for evangelicals. For one thing, the Methodist liberal establishment did not even want to admit evangelicals were evangelicals. When I went to the head of the chapel committee at my Methodist seminary and asked if we might be able to include some evangelicals among the chapel speakers, he informed me everyone at the seminary was evangelical, and just who did I have in mind. When I explained he replied, “I believe you are talking about fundamentalists and we’re not going to share our pulpit with any of them.”

When Billy Graham came to Chicago and some of us wanted to ask Graham to visit our campus, the president of the school said, “No, because we do not wish to be identified with that kind of Christianity.”

The prevailing seminary and liberal institutional view was that “fundamentalism” was an approach to Christianity of a former day and was not appropriate for Methodists, neither in the present day nor for the future. Methodism was set in its direction. In a survey of seminaries conducted in 1926, every single Methodist seminary had declared its orientation as “modernist.” As early as June 1926, the Christian Century had declared that the modernist-fundamentalist war was over and fundamentalism had lost. It announced its obituary in these words: “It is henceforth to be a disappearing quantity in American religious life, while our churches go on to larger issues.”

Other larger issues in the 1960s included war, race, COCU, economic disparity, Death of God, the Secular City, liberation theology, rising feminism, process theology, and existentialism.

Institutional liberalism was out of touch – and I was frequently bemused in those seminary days by how out of touch it was. When someone mentioned revivals in seminary, the professor indicated that revivals were a thing of the past and he had not heard of a Methodist church that had held a revival for years.

It so happened that a friend of mine from Taylor University days, Jay Kesler, was at that very moment holding a revival and would preach at 152 revivals during his years at college, most of them in Methodist churches. Youth for Christ was on the scene, as was Campus Crusade and Billy Graham’s ministry. Evangelical schools were flourishing.

That was the situation when Chuck Keysor, a pastor from Elgin, Illinois, wrote an article for the July 19, 1966 issue of the denomination-wide Christian Advocate entitled, “Methodism’s Silent Minority.”

“Within the Methodist church in the United States is a silent minority group,” Keysor wrote. “It is not represented in the higher councils of the church. Its members seem to have little influence in Nashville, Evanston, or on Riverside Drive. Its concepts are often abhorrent to Methodist officialdom at annual conference and national levels.

“I speak of those Methodists who are variously called ‘evangelicals’ or ‘conservatives’ or ‘fundamentalists.’ A more accurate description is ‘orthodox,’ for these brethren hold a traditional understanding of Christian faith.”

Keysor explained in the article that this minority was often accused of being narrow-minded, naïve, contentious, and potentially schismatic. This was unfortunate because these people loved the church and had been faithful Methodists all their lives.

In making his case Keysor mentioned that there were many more of them than official Methodism was counting. At least 10,000 churches, for example, were using Bible-based Sunday school material instead of the official Methodist material. The 10,000 figures brought strong reaction and led to charges of irresponsibility and plain out lying. But Keysor knew whereof he spoke.

Trained as a journalist he had served as managing editor of Together magazine, Methodism’s popular family magazine. He had then been converted in a Billy Graham crusade and spent some years as an editor at David C. Cook, an evangelical publisher. The 10,000 churches figure had come from his years at Cook. He knew more about what churches were not using Methodist materials than did the Nashville editors at the time. At Cook, he also became aware of the evangelical world.

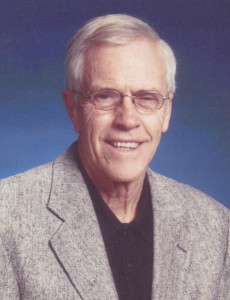

Riley B. Case

Keysor’s article drew more responses than any other article Christian Advocate had ever published. The responses followed a common theme: “You have spoken our mind. We didn’t know there were others who believed like we did. What can we do?” Keysor called together some of the most enthusiastic responders. Hardly any of those early responders would be recognized today. Nor were they recognized then. They, after all, were the “silent minority.” They were the little people, the populists — rural church pastors, long-suffering lay persons, conference evangelists.

The obvious step forward for Keysor, a trained journalist, was for a magazine. A notable voice of encouragment was from Spurgeon Dunnam of Texas Methodist (eventually becoming The United Methodist Reporter). In the September 6, 1968, issue Dunnam editorialized that the church needed a conservative voice. The liberal voice was presented by the official Methodist press with Christian Advocate and Concern (Dunnam was one who believed that an official “press” was too often public relations-oriented and thus reflected the views of the leadership) but there was no conservative voice and Good News could fill the void.

“The Texas Methodist is pleased to make known to its readers that within the past year a responsible ‘conservative’ journal of opinion has been born within the United Methodist Church. It is called simply Good News, and we think it is just that.”

Coming out of exile. Would it be possible for evangelicals to get together? On August 26, 1970, the first national convocation was held. Sixteen hundred registered and crowds on some evenings swelled to over 3,000. The speakers included luminaries such as evangelist Tom Skinner, Bishop Gerald Kennedy, Harold Ball of Campus Crusade, and E. Stanley Jones. Dr. K. Morgan Edwards of Claremont School of Theology gave the keynote address. People who came to the convocation prayed and hugged and worshipped and wept and said “Amen” and “Hallelujah” without fear of disapproving stares around them. Twenty percent of the attendees were between 20 and 35 years old. Keysor wrote of the event, “We are coming out of exile.”

The critics cried, “divisive.” Again Spurgeon Dunnam responded. In an editorial titled “Constructive Divisiveness” Dunnam commented:

“The question which remains is: are the evangelicals a divisive force within the church? Yes, they are divisive. Divisive in the same way Jesus was in first century Judaism. Divisive in the same way Martin Luther was to sixteenth century Catholicism. Divisive in the same way that John Wesley was to eighteen century Anglicanism. And, strangely enough, divisive in the same way that many liberal ‘church renewalists’ are to Methodism in our own day.

“A survey of Methodism in America today reveals these basic thrusts. One is devoted primarily to the status quo. To these, the institution called Methodism is given first priority. It must be protected at all costs from any threat of major change in direction….

“The other two forces do question the theological soundness of institutional loyalty for its own sake. The progressive, renewalist force has properly prodded the Church to take seriously the social implications of the Christian gospel…. The more conservative, evangelical force is prodding the church to take with renewed seriousness its commitment to the basic tenets of our faith…”

When Dunnam was writing those words, the Reporter was reaching a million persons per week and was the largest-circulation religious paper in the world. Under Dunnam’s leadership, it investigated both liberal and conservative activities. Even when Dunnam disagreed with Good News, he always treated us with integrity.

In the midst of all this activity, Good News was not on solid ground financially and staff-wise. Then a providential person and offer came on the scene. Dr. Dennis Kinlaw, president of Asbury College in Wilmore, Kentucky, was cheering Good News on from the sidelines, but he came up with an idea to help Good News as well as Asbury College. He offered Keysor a job of teaching journalism part-time at Asbury with the understanding that the rest of his time could be used to edit the magazine. For the fledgling Good News board it was an answer to prayer. The move was made in the summer of 1972.

At the time Good News was not even recognized as an advocacy group in the church. Engage magazine listed the special interest groups at the 1972 General Conference: Black Methodists for Church Renewal, the Women’s Caucus, the Young Adult Caucus, the Youth Caucus, the Gay Caucus. There was no evangelical caucus. By 1976 things had changed. Good News was able to generate 11,000 petitions, most having to do with maintaining the Discipline’s stand on marriage and sexuality in response to an aggressive progressive agenda.

Keysor knew that these controversial cultural and theological issues would divide the church. The institutionalists responded with the kind of language that would be used frequently of evangelicals of the Good News-type in the years to come: “reactionary,” “out-of-step,” “fundamentalist,” “highly subsidized,” “hateful,” “seeking to undermine the church’s social witness,” “not serving the interests of the church.”

One critic, Marcuis E. Taber, summed up the accusations in an article that appeared in the Christian Advocate (May 13, 1971) entitled, “An Ex-Fundamentlist Looks at the Silent Minority.” According to Tabor, Good News was an “ultrafundamentalist” movement with an emphasis on literalism and minute rules which was opposed to the spirit of Jesus. It had no future in a thinking world.

The Christian Advocate gave Keysor a chance to respond and so he did in the fall of 1971. The response, classic Keysor, was perceptive, straightforward and prophetic. It said basically that Tabor and others were reading the church situation wrongly. Storms were battering the UM Church and soon it will be forced to jettison more of its proud “liberal” superstructure. Meanwhile evangelical renewal was taking place: the charismatic movement, the Jesus People, Campus Crusade, stirrings in the church overseas. If there was a right side of history, it was with evangelical renewal. This is what it meant to be “a new church for a new world.”

Was Keysor right? Looking back on our history, this is worth a discussion.

Riley B. Case is the author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History (Abingdon). He is a retired United Methodist clergy person from the Indiana Annual Conference, the associate director of the Confessing Movement, and a lifetime member of the Good News Board of Directors.

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Elizabeth Glass Turner-

By Elizabeth Glass Turner-

Now there was a Pharisee named Nicodemus, a leader of the Jews. He came to Jesus by night and said to him, “Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God; for no one can do these signs that you do apart from the presence of God.” … Jesus answered, “Very truly, I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit. … Do not be astonished that I said to you, ‘You must be born from above.’ The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.” – John 3:1, 2,5,7,8

Recently I watched an enormous convergence of red-winged blackbirds dip and sway outside my second floor study window, unknowingly choreographing a mid-air dance to the Bach cello suites I was enjoying. Like a school of fish, they moved in unfathomable unity and rhythm, following currents I could not see. What made them land and take off, beat their wings or soar, I could not tell. What ballet dancers take years to perfect – spry grace, effortless motion, pivots, wheels and stops – these birds know by nature, from their first tumble out of the nest. I can become a skilled birdwatcher and still be unable to anticipate which way a flock of thousands will turn at the last second.

I cannot fathom. I can only witness.

I can make a lifetime’s study of birds and their habits and still not know which branch they will choose when it is time to build a nest. I can give my mind to ornithology and still not predict where in a shorn field a cloud of blackbirds will choose to land. I cannot fathom. I can only witness.

It fascinates me when Jesus speaks of the Holy Spirit. It is, as it were, an insider’s view. “Do not be astonished that I said to you, ‘You must be born from above.’ The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.” Jesus speaks to the learned religious leader Nicodemus late at night, out of sight of prying, judgmental eyes. He gives Nicodemus a sneak peek of Pentecost, and Nicodemus simply doesn’t understand. His world is temple-centered, sacrifice-marked, roped-off Holy of Holies encased in thick, impenetrable curtain. Nicodemus is surprised quite naturally. It would be odd if Nicodemus weren’t astonished at Jesus’ words. But we see Jesus keep a wry upper hand by gentle instruction. “Do not be astonished.” And then – “the wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.”

Nicodemus, you won’t be able to fathom. But you will be able to witness. And when you’re born of the Spirit, that’s the natural state of things. Are you ready for a new normal? It’s like you’re going to be born all over again.

Jesus could speak with authority about the coming normal. The Holy Spirit always – always – witnesses back to Christ. The person of the Holy Spirit isn’t an untethered Holy Ghost, freelancing the Godhead in a hit-and-miss fashion, nor is the Holy Spirit confined to showing up when a priest prays over the elements of the Eucharist. The Holy Spirit is always shaping and molding into the image of Christ: the Holy Spirit helps us love as Christ loves, act as Christ acted, as individuals and corporately, in your soul and mine, in our nation’s soul and the world. Pastors pray the Holy Spirit will come upon “us here, and make this be for us the Body and Blood of Christ”: however we understand it, we believe the Holy Spirit even makes bread more like Jesus.

You and I can understand this truly but not fully or completely. Right now we see dimly, after all; then, face to face. We may grasp Truth without fathoming it.

You cannot fathom. You can only witness.

I know people who have, by the grace of God, been the means of healing another person in decisive and supernatural ways. I know people who have, by the grace of God, received physical healing through the means of another person, in decisive and supernatural ways. I cannot hope to fathom it.

But I can bear witness.

I can’t explain how the prison doors shook open in the book of Acts. I can’t explain how a devastated Methodist believer from an AME church stands and weeps and says, “I forgive you” to a stony young man who shot and killed members of a Bible study. I can’t explain how an embarrassed but ill Catholic priest sneaks to a charismatic healing service (sans collar) and comes away well.

I cannot fathom. I can only witness.

I can’t fathom how God sometimes orchestrates circumstances in my life with astonishing, miraculous swiftness, in ways that couldn’t have happened otherwise. And I don’t know why a banner of blackbirds drifting through the air rises and lowers, sinks and elevates. They shift and merge, depart and gather. I witness their movement, even if I don’t comprehend it. I can speak of it truly, even if I can’t master its science – or improvisation.

“Do not be astonished that I said to you, ‘You must be born from above.’ The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.”

We are called to watch out for the Spirit, as ardently as an amateur birdwatcher with binoculars slung around her neck, guide book in hand. We’re called to be ready to see the Spirit in action. We’re called to make a space for the Spirit, to pray, as 24/7 Prayer Movement founder Pete Grieg urges, “come on!” We’re called to stand on the windy porch, eyes on the sky, scanning the horizon.

But am I as agile as a red-winged blackbird? Am I as quick to respond to the current of the Holy Spirit? Can I dip and dive, rise and soar moment by moment, season by season, so that I fly with such quickness, such ready adaptability that my motions mimic the thousands of others’ around me? What may feel clumsy or wooden at first may yet become intuitive and natural. And while I may not be conscious of the ways my motions or seasons appear to others, when put next to the rest of the flocks’, a grand avian ballet may emerge.

And isn’t that the Body of Christ? This nimble flock of little birds, following the Spirit’s movements, no winged creature able to say to the other, “I don’t need you”? “Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; and there are varieties of services, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of activities, but it is the same God who activates all of them in everyone. To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good” (I Corinthians 12:4-7). You cannot fathom. You can only witness, in your speech and soaring.

As this publication reaches its sage milestone of 50 years, we have the joy of celebrating many seasons of faithful witness to the work of the Holy Spirit consistently pointing to the person of Christ. We don’t just celebrate the founder, one person, or even an institution, but rather, we get to celebrate God’s faithfulness.

At the same time, we are compelled not only to celebrate how we started as nimble and responsive, but also how we may live into the future with elastic, intuitive readiness to the movements of the Holy Spirit.

This is essential. It is a full stop. We cannot rely on outwitting our opponents. We cannot rely on outfundraising those with whom we disagree. We cannot rely on outlasting our rivals. Wit and resources and tenacity are important, but they are not the most important. They are not indispensable to any movement. It is dangerously tempting to rely on what we know – on facts, figures, data, on our own history, heritage, contributions. That was the move that experienced, educated Nicodemus made.

Nicodemus, you won’t be able to fathom. But you will be able to witness. And when you’re born of the Spirit, that’s the natural state of things. Are you ready for a new normal? It’s like you’re going to be born all over again. You’ll have to relearn how to walk and talk, how to eat and sleep. Are you ready for that? To be as trusting and dependent as a newborn?

Well – are you?

Sometimes artists stumble into Truths bigger than they’re able to comprehend. It strikes me that the lyrics from Paul McCartney could easily mimic Jesus’ thoughts as he watched Nicodemus walk towards him in the dark, one late night:

“Blackbird singing in the dead of night/ Take these broken wings and learn to fly/ All your life/ You were only waiting for this moment to arise.

“Blackbird singing in the dead of night/ Take these sunken eyes and learn to see/ All your life/ You were only waiting for this moment to be free.”

Jesus said, “The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.”

Are you ready, Nicodemus?

Well?

Are you ready?

Elizabeth Glass Turner is a writer and Associate Director for Community and Creative Development for World Methodist Evangelism. She is managing editor of www.wesleyanaccent.com and a frequent and beloved contributor to Good News.

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

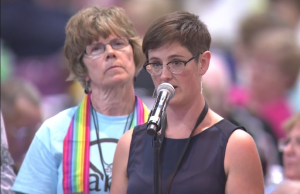

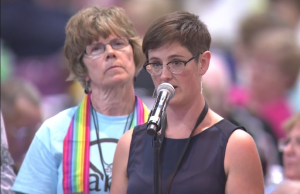

The Rev. Anna Blaedel: “I am a self-avowed practicing homosexual.”

Three clergypersons from the Iowa Annual Conference of The United Methodist Church have filed a formal complaint against their former episcopal leader, Bishop Julius Trimble, for “disobedience to the order and discipline of The United Methodist Church” and an unwillingness to do the work of ministry entailed by a bishop. Trimble has recently been reassigned to the Indiana Annual Conference. The complaint from the Revs. Craig Peters, Mike Morgan, and John Gaulke was sent to Bishop Gregory Palmer and Bishop Hee-Soo Jung, president and secretary of the North Central Jurisdiction College of Bishops. Fourteen additional lay and clergy members of the Iowa Annual Conference added their names to the complaint from Peters, Morgan, and Gaulke.

The focus of the complaint centers on the public testimony of the Rev. Anna Blaedel, a campus minister at the University of Iowa Wesley Center, when she announced before her colleagues at the Iowa Annual Conference in June, “I am a self-avowed practicing homosexual. Or in my language, I am out, queer, partnered, clergy.”

In response to Blaedel’s public comments, the clergypersons filed a complaint against the campus minister. After one supervisory response meeting, the bishop was unsuccessful in obtaining a mutually agreeable just resolution. Bishop Trimble summarily – and incorrectly – dismissed the complaint against the Rev. Blaedel and reappointed her as an ordained clergyperson.

The Iowa ministers who filed the complaint point out that Bishop Trimble does not have the right – according to the Judicial Council – to “legally negate, ignore, or violate provisions of the Discipline with which [he] disagrees, even when the disagreements are based upon conscientious objections to those provisions” (Decision 886).

The concerned clergypersons also contend that Bishop Trimble’s failure to provide a written explanation of the dismissal of the complaints is a failure to do the work of ministry of a bishop. “The disruption caused by Rev. Blaedel’s admission and the bishop’s dismissal of the complaint has been severe,” write the three pastors, “impacting local church members and clergy across the Iowa Annual Conference who do not understand why the clear standards of our Discipline have been ignored. Bishop Trimble made no provision for a process of healing, which constitutes a failure to do the work of ministry and a violation of the requirements of the Discipline.”

In his negligence to the process of the handling complaints, the ministers contend that Bishop Trimble failed to consult with – or even notify – the complainants before dismissing the complaint.

“We are reluctant to file this complaint and do so out of love for our church and its integrity,” state the clergypersons. “The integrity and trustworthiness of the church is undermined when a bishop chooses to arbitrarily ignore violations of our covenant life, especially when those violations are as public as Rev. Blaedel’s.”

![Plunge in Worship Attendance]()

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Walter Fenton-

By Walter Fenton-

The United Methodist Church’s General Council on Finance and Administration (GCFA) reported a 2.9 percent decline in weekly worship attendance from 2014 to 2015. Some observers merely shrug when they hear about a 2.9 percent loss. It seems deceptively inconsequential.

The stark truth is that a 2.9 percent decline means a loss of 82,313 worshippers, the largest loss in the denomination’s 48-year history. On average, UM local churches in the U.S. collectively welcomed 2,832,239 to worship services each weekend in 2014. That number dropped to 2,749,926 in 2015.

The figure is considered a key indicator of the health and vitality of the church, and it is an important number for helping the GCFA construct the quadrennial budgets for the general church. Last year, when the GCFA learned that average worship attendance fell 2.6 percent from 2013 to 2014, it revised downward its budget proposals for the 2016 General Conference delegates.

While a 2.9 percent decline from one year to the next does not immediately threaten the church, cumulative drops of two percent or more are cause for grave concern. In four of the last six years the denomination has seen drops above that threshold.

Throughout much of the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, average worship attendance declined, but not precipitously so. While the rate dropped overall, there were years when average worship attendance actually increased. (The last time the denomination registered an increase in worship attendance was 2001, when the figure grew by 1.7 percent. Many church statisticians considered that rise an anomaly due to a resurgent, but brief interest in church attendance shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The UM Church was not alone in seeing an increase in 2001.)

“Between 1974 and 2002, we lost an average of 4,720 in worship attendance per year,” said Dr. Don House, a professional economist and former chair of GCFA’s Economic Advisory Committee. “But a major shift occurred in 2002. The rate skyrocketed to an annual rate of 52,383 between 2002 and 2012, and now we’ve seen losses of 62,571 (2012-2013), 75,671 (2013-2014), and 82,313 between 2014 and 2015. This is not sustainable.”

Generally, declining rates of worship attendance have a knock-on effect. As local churches see fewer and fewer worshippers, they find it harder to stem their declines. Eventually, they discover they can no longer afford a full-time pastor, which only exacerbates their situations.

More broadly, the denomination then struggles to recruit new pastors, particularly younger ones with families and college debt. People considering full-time ministry justifiably wonder if there would be a local church appointment available that could pay a decent salary with health and pension benefits.

Calculations like this ultimately impact the church’s seminaries in declining enrollments, leading to reduced staffing at the institutions, and even threatening their viability. In short, the drop in worship attendance erodes the very infrastructure many believe is necessary to reverse the downward trend.

In a 2014 report to the GCFA and the Connectional Table, the denomination’s highest administrative body, House warned that the church needed to quickly adopt a credible and metrics driven plan to arrest the plunge in worship attendance. If it failed to do so, he projected that by 2030 the denomination would slide into permanent decline and face collapse by 2050.

When House prepared his report he possessed attendance records through 2013. Based on the figures at hand he projected an annual rate of decline of 1.76 percent, but the numbers from the last three years (2.1, 2.6, and 2.9) are well above that rate.

“If we experience a growing rate of decline, as demonstrated since 2012,” said House, “our window for a turnaround strategy will be shorter than I originally projected. We cannot maintain the connection unless we are able to implement and fund a strategy within the next 14 years.”

All five jurisdictions in the U.S. experienced average worship attendance losses in 2015. The Western jurisdiction led the way with a drop of 3.6 percent followed by the Northeastern (3.5), North Central (3.2), South Central (2.8), and the Southeastern (2.5).

Four of the 56 U.S. annual conferences actually bucked the downward trend with increases in attendance: Yellowstone (9.5 percent), West Virginia (4.3), Dakotas (1.7), and Peninsula-Delaware (1.1).

Conferences with the steepest losses were: Eastern Pennsylvania (7.3 percent), New Mexico (6.8), Susquehanna (5.7), and Dessert Southwest (5.4). Between 2014 and 2015 the Eastern Pennsylvania Annual Conference saw one of its largest and fastest growing local churches exit the denomination.

Various reasons for the decline in attendance have been cited.

There is general agreement that many local churches are located in areas where the general population has been declining for years (e.g., western New York and Pennsylvania, and across the upper Midwest and Great Plains states). When these churches were planted in the 19th century their locations made good sense, but now, due to declining population, they are difficult to sustain. It is also true that UM Church members are an aging population, so some of the decline in average worship attendance is simply due to attrition.

These natural declines are not being offset by local church growth in the major metropolitan areas clustered along the coasts, across the south, and in other urban areas where other denominations and non-denominational churches are either holding their own or seeing increases. For instance, the UM Church has only a few large, growing congregations in the densely populated urban areas of the northeast and the west.

Of the approximately 32,100 local UM churches in the U.S., 76 percent (24,654) average less than 100 in attendance, and nearly 70 percent (16,909) of those actually average less than 50 on Sunday morning. Local congregations below that threshold are often challenged to afford a full-time pastor or to find the resources necessary for a sustained plan of evangelization.

Beyond the reasons cited above, there is considerable debate as to why worship attendance has fallen for the past 14 years straight, and why the rate has accelerated so dramatically in the past five.

Many progressives and some centrists argue the church is woefully out of step with the broader culture, particularly with millennials. They claim the church is actually alienating many people with its stands on social issues, particularly those having to do with sexual ethics and marriage.

Traditionalists and other centrists argue the church has lost its evangelical zeal, and also claim the Council of Bishops’ public failures to maintain the good order of the church has undermined local church effectiveness, sapped the morale of clergy and laity who have come to distrust their leaders, and driven members away from its congregations.

Despite the record loss for the denomination, many local churches continue to thrive, grow, and show signs of health and vitality in the ministries they undertake every day.

“I am confident,” said the Rev. Rob Renfroe, president of Good News, “that when we United Methodists are at our best, we have a message that will win people to Christ, transform lives, and send out dedicated disciples to the last, the least, and the lost. I’ve seen it happen over and over again in many different places. But given the crisis we are facing, we must be prepared, going forward, to consider bold ideas and implement major structural changes.”

Walter Fenton is a United Methodist clergy person and an analyst for Good News.

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Photo provided by danielstrickland.com.

By Courtney Lott-

Chaos gets a bad rap. We cling to order and calm, presenting nice, tidy images of ourselves worthy of Facebook and Instagram and Pinterest. Behind them we hide, loathe to let others see what’s on the other side of the curtain. Yet, it’s often when things are upturned, broken, and exposed that we experience true growth and change. In her book, A Beautiful Mess, author Danielle Strickland suggests that God actually uses chaos to transform our lives and draw us closer to him.

A major in The Salvation Army in Los Angeles and an Ambassador for the global anti-trafficking campaign Stop the Traffik, Strickland knows how messy life can get better than most. Through her own encounter with the Lord and her ministry to brothels, she is intensely familiar with the ugly, dirty chaos of this world. Rather than run from it, Strickland chooses to embrace it.

“My experience of life with God is messy,” she says in her introduction. “It’s a mix of failure and success, courage and fear, faith and doubt. It’s-well, a beautiful mess…It’s beautiful because it’s a witness to the creative design of God’s love in the here and now of our lives. My life doesn’t look anything like it once did…I’ve been re-created by a designer who loves to recycle.”

This serves as a thesis statement for the rest of the book. What follows are stories of God working through the chaos of people’s lives to accomplish his good purposes. Interwoven between these is Strickland’s ongoing exhortation to embrace the messes we encounter rather than try to hide or cover them up.

One of the strongest points of A Beautiful Mess is the probing questions Strickland asks, and she starts right out of the gate in the first chapter. “What if the pursuit of order has created a love of the status quo and has removed the passion for justice? What if we have made a friend of comfort instead of change and as a result removed ourselves from the responsibility that demands that we fight for change to happen?”

Throughout the book, Strickland continues to prod the reader with these types of questions. They cause the audience to stop, to think, to reconsider. In harmony with her premise, this upends the nice little boxes we might have stacked neatly in our minds, creating the kind of discomfort that challenges long held beliefs. Somewhat ironically, she also adds orderly numbered questions at the end of each chapter as well, making it easy to use in a discussion group.

Chaos, Strickland says, is necessary to create something; and, in fact, an over devotion to order actually leads to breakdown. She writes, “If instead of clinging desperately to order we allow God to set the priorities, then the divine can and does speak a different kind of order into existence that promises permanent and lasting meaning for us personally and in the work that we are a part of.”

It can feel like chaos to give up control, to wait on the Lord’s voice and His timing, and it requires a healthy dose of courage. According to Strickland, however, it is only when we wrench our grip from the wheel and hand it over to the Lord that we can enter real life. Of the many stories the author tells in A Beautiful Mess, one of the most profound is a story that starts with an affair. After catching her husband being unfaithful, a friend of Strickland’s found her entire life turned upside down. Yet amidst the chaos and mess, she sought out the Lord. It was then that he led her to Africa. From what seemed to be a dead end, God used this woman to serve widows and orphans in desperate need of her gifts. Stories like this remind the audience that there is a bigger picture; that on the other side of messy suffering is a new path, renewed life.

“What is emerging from her chaos is something so beautiful and rich and different than her life would have been,” writes Strickland. “She now has the ability to look back and see that even the chaos was an opportunity to see God’s order emerge in her life. Even the darkness helped her [move] toward God’s Divine Order for her life.”

Chaos also often uncovers the truth we hide from, Strickland says. An experience in Russia just after the collapse of the Soviet Union taught her about the failures of scientific and orderly modernity to answer the deep internal questions. Strickland learned from her Russian translator, Olga, that the government had fed the people many lies to make them believe that things were good. Everything appeared neat and tidy on the outside, but the eventual collapse made it evident that this was not true. The citizens of the Soviet Union chose to believe the lies they were fed until the chaos forced them to see the truth.

Strickland writes, “It is sometimes simply easier to believe that things are ordered, reasonable, predictable, and completely under our control. But the reality of our world is that it is unpredictable, often random and unreasonable, chaotic and completely out of our control. And that’s when modernity’s promises run empty and its progress reports run dry.”

This is not limited to secular governments, Strickland says. The church also often trips into the same pitfalls, settling for “whitewashed tombs” rather than accepting the kind of chaos that asks hard questions and risks failure. “The truth would rather embrace honest chaos than continue to whitewash the tombs of our culture so we die looking good,” Strickland writes. “It’s really about allowing chaos to show a bit, and even enjoy it.”

Finally, Strickland says that chaos can actually bring light to darkness and allow us to join with God to create things. Injustice casts a pall over our world and when we seek to bring an end to it, a mess often ensues. As uncomfortable as this might be, it is necessary if we wish to make any kind of progress, if we want to join God in bringing his kingdom here on earth as it is in heaven. Strickland describes it beautifully. “We need a ‘curtains being pulled back in the morning’ moment where light or revelation floods in.” If we’re standing still in fear of the chaos, she says, we will never experience this kind of moment.

Strickland concludes A Beautiful Mess by encouraging the reader to create a timeline in which to track times of chaos within one’s life. This, she says, will help identify the process of God’s “Divine Order”, of how he uses the mess to bring us into his light. “We get to be a part of this incredible work of beauty – this art called life,” she writes. “And then we rest. We step back and breathe in the beauty of a love-filled, creative God. A God who uses every shade and vibrancy of colour to re-create our lives in ways we could never have imagined or dreamed. We get to stop working, and celebrate the incredible truth that we are, all of us, a beautiful mess.”

Courtney Lott is the editorial assistant at Good News.

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Thomas Lambrecht-

By Thomas Lambrecht-

After an agonizingly long period of formation, the Bishops’ Commission on a Way Forward for The United Methodist Church began its work in December. The commission consists of 32 members reflecting the broad geographical, ethnic, and theological diversity within United Methodism.

The commission is being moderated by three bishops, Sandra Steiner Ball (West Virginia), Kenneth Carter (Florida), and David Yemba (Democratic Republic of Congo). The members of the commission include eight bishops (not counting the moderators), 13 clergy (two deacons and 11 elders), and 11 laity. Geographically, one-third of the commission is from outside the United States (seven from Africa, two each from Europe and the Philippines).

The commission’s deliberations began with a conference call in mid-December. Roughly a half-dozen face-to-face meetings are tentatively planned in 2017, with more in 2018. The investment of time will be significant, with meetings planned to last 2-1/2 to 3-1/2 days each. It is expected that commissioners will do assigned reading and other background work in between meetings.

The purpose of the commission was set forth in the bishops’ statement to the 2016 General Conference outlining their call to find a new way forward in unity. The commission is charged with “discerning and proposing a way forward through the present impasse related to human sexuality and the consequent questions about unity and covenant” (October 24 press release). Highlights of that call include:

• To “seek a way forward for profound unity on human sexuality and other matters”

• To consider a way for a “deep unity [that] allows for a variety of expressions to co-exist in one church”

• “To lead the church toward new behaviors, a new way of being and new forms and structures which allow a unity of our mission of ‘making disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world’ while allowing for differing expressions as a global church”

• To deal with the subject of human sexuality, all the legislation regarding sexuality that was referred by the 2016 General Conference to this commission, and “to develop a complete examination and possible revision of every paragraph in our Book of Discipline regarding human sexuality.” Many assume that this means the commission will be looking for ways to delete or weaken the church’s paragraphs on sexuality. But this purpose could just as easily mean a strengthening, clarifying, and restating of the church’s long-standing teaching on sexuality and marriage. In any case, revisions are “possible,” not mandated.

The bishops, particularly the moderators, have committed to regularly communicate with the church about the work of the commission. They will issue statements monthly on the commission’s progress, which reports began last October even before the naming of the commission.

The commission faces some steep challenges. People from all over the world, speaking a variety of languages, and coming from diverse personal backgrounds, will need to forge relationships that can lead to trust and open communication. We will need to address a topic that is fraught with deep emotional and personal impact. We will need to attempt to bridge a theological divide in our church that is more like a chasm. We will need to consider the impact of the commission’s recommendations on every single United Methodist, every congregation, and multiple regions and cultures around the world.

The commission comes into being at a time when significant parts of the U.S. church have determined to live in violation of the requirements of our Book of Discipline as established by the worldwide church in General Conference. That continued disobedience endangers the church’s unity and can influence the very nature of what it means to be United Methodist. Advocates for such disobedience are members of the commission, as are persons who staunchly defend the church’s current teachings and requirements around sexuality, marriage, and ordination. How will these differences be bridged?

The commission’s work also takes place at the same time that other significant initiatives are moving forward in the church. One is the effort to delineate a global Book of Discipline that all United Methodists must live by, while allowing annual conferences and perhaps jurisdictions to adapt other parts of the Discipline to their local context. A second initiative is the development of entirely new Social Principles that are globally applicable and couched in more understandable language. These and other initiatives will need to be coordinated with the commission’s work, so that the recommendations of all groups will be coherent with each other.

The bishops of the church are coordinating a parallel effort in the grassroots of the church to engage in dialogue around the topic of human sexuality and its implications for the unity of the church.

Given the broad scope and significance of the commission’s work and the challenges it faces, the bishops have requested that prayer be a central focus of the commissioners, as well as the general church. Please remember to regularly lift up the commissioners and our work, as we seek a Christ-honoring way forward. Pray for God’s grace, not only upon the deliberations of the commission, but upon the commissioners’ lives, as we sacrifice significant time away from family, work, and ministry and experience the demands of international travel in order to devote ourselves to this important task.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson, vice president of Good News, and a member of the Bishops’ Commission on a Way Forward for The United Methodist Church.