by Steve | Mar 24, 2017 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Walter Fenton-

A congregation in Wichita, Kansas, that averages 350 in worship has voted to leave The United Methodist Church. As a satellite campus of Asbury UM Church, the congregation announced its decision on Sunday, March 19.

“Some pastors and people are weary of all the defiance and unaccountability in the denomination,” said the Rev. Rick Just, senior pastor of Asbury UM Church. “While we at the central campus are praying and waiting for the Commission on a Way Forward to provide leadership and guidance during this unsettling time, Pastor Aaron Wallace, the leadership team, and the congregation at our west campus reached the conclusion that the ongoing battles in the denomination are a distraction from the kind of kingdom work they want to do.”

Asbury UM Church planted its west campus site 10 years ago in an effort to reach unchurched people and younger families on Wichita’s growing west side. The satellite congregation grew quickly and attracted its target audience. The west campus is filled with people in their 30s and 40s, and boasts thriving programs for children and youth. The central campus also remains one of the healthiest and most evangelistic churches in the Great Plains Annual Conference.

“We are sad about their departure,” said Just, “but church leaders have been going their separate ways to do ministry since Peter and Paul took different paths. Asbury is proud of what we accomplished with our west campus. We’re not bitter about the situation, and we foresee partnership opportunities with Pastor Wallace and his congregation as we all work to make disciples of Jesus Christ.”

In a media statement shared with Good News, Wallace acknowledged his “struggle with some of the conflict that has been occurring in the life of the denomination.”

According to an article by Todd Seifert, Communication Director for the Great Plains Annual Conference, Bishop Ruben Saenz, Jr., the episcopal leader in the area, said, “Clergy and laity throughout The United Methodist Church are in a season of waiting and discernment as members of the denomination experience varying levels of frustration with the impasse on human sexuality and the unity of the church. The denomination is awaiting a ruling from the Judicial Council on the election of an openly gay bishop serving in the Western Jurisdiction and is following closely the progress of the Commission on a Way Forward, a group appointed by the Council of Bishops to review language related to human sexuality in the Book of Discipline.”

Word of the congregation’s decision comes just weeks after two large UM churches in Mississippi voted to leave the denomination. Both congregations are still in conversations with Mississippi Annual Conference leaders regarding the terms of their exits.

“I fear these departures are just the most visible manifestations of what is going on across the connection,” said the Rev. Rob Renfroe, President of Good News. “People hoped our bishops would stand up and defend our church’s teachings on marriage and its sexual ethics, instead, they’ve witnessed a train of defiance and dysfunction. My guess is many more rank-and-file United Methodists are just simply walking away from local churches. It’s a sad indictment of many of our leaders.”

Walter Fenton is a United Methodist clergy person and an analyst for Good News.

by Steve | Mar 24, 2017 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Walter Fenton-

By Walter Fenton-

Methodists down through the decades are famous for being “methodical” and giving attention to detail. From the very beginning, John Wesley baked into the Methodist system a regular accounting of membership and attendance in small groups. In order to participate in a worship service, Methodist members had to regularly attend small groups and receive a ticket for admittance!

Today, church membership is a vital statistic used to track the health of the church. It is often a factor in how much money a local church is asked to pay for denominational missions and administrative expenses. The number of General Conference delegates and the number of bishops are determined by how many members reside in a given area.

But one must ask, given the importance of membership numbers, are they reliable? It is risky to draw detailed conclusions based on numbers that may not be accurate.

In a recent blog post, Dr. David A. Scott, Director of Mission Theology for the General Board on Global Ministries, reports a potentially groundbreaking news story that has eluded the United Methodist media and all other denominational analysts regarding explosive UM Church membership growth among ethnic minority groups in the U.S.

According to Scott, every single ethnic minority group has experienced dramatic growth between 1996 and 2016 (Scott has since informed me that the numbers he provides for 2016, are actually totals for 2014). If these statistics were proven to be solid, this would be a justifiable cause for denomination-wide rejoicing. It would also be one of the most important cultural/ethnic/racial religion stories in the news.

One of the iron-clad rules for journalism, however, is that when statistics look fantastically irregular, they are often worth a second look.

For example, is it possible that overall United Methodist membership and attendance in the United States could be declining at an alarming rate and yet African-American membership within the denomination has skyrocketed 37 percent?

If those statistics were solid, there would be a remarkable story to tell – and church growth leaders would be telling it. After all, the UM Church in the U.S. has not seen an identifiable 37 percent membership increase in years.

The same could be said of the 78 percent increase among United Methodist Hispanics. That would be stunning and a great cause for rejoicing. The same goes for the 106 percent increase of Asian-American United Methodists, the 101 percent increase of Pacific Islanders, and the 23 percent increase among Native American United Methodists.

Based on alleged remarkable gains for minority groups and the drop among Caucasian membership, Scott concludes that Caucasians need to “acknowledge their whiteness and repent of the ways in which their thinking has been shaped by race and not the gospel,” so they can “learn from their sisters and brothers of color.”

Cross-cultural learning is always a worthy task, but Scott’s grounding this insight in the membership numbers he cites is a dubious one. This is true because the UM Church faces a variety of conundrums when it comes to compiling and reporting membership data.

Pastors, who lead its approximately 32,100 local churches in U.S., are ultimately responsible for submitting membership and attendance data to their annual conferences and the denomination’s General Council on Finance and Administration. The ways clergypersons manage local church membership rolls vary dramatically. Some are so fastidious they would warm John Wesley’s heart. Others, as one colleague wryly noted, “Have other fish to fry.” Most fall somewhere in between.

Clergy also vary widely in the way they receive members into the denomination. Some pastors require people to attend anywhere from four to a dozen or more class sessions on doctrine, history, and polity before joining the church. Others are happy to receive people as members at the close of a worship service after they have attended a time or two.

And while pastors do dutifully report membership losses many are loath to do so. They believe it reflects poorly on their leadership and, not without some justification, believe it will impact their next appointment. And of course district superintendents and bishops are not immune to a certain reticence around reporting losses either. On balance, there are many compelling reasons for pastors and church leaders to not be too meticulous when it comes to membership numbers.

Consequently, many local churches carry far more members on their rolls than actually attend their services. For instance, several of the denomination’s 100 largest churches see, on average, just 10 to 15 percent of their members at weekly worship. In 2015, over 60 percent of the UM Church’s 7.1 million members were not in attendance on any given Sunday.

None of this would be particularly disconcerting were it not for the fact that the membership numbers do figure significantly in different ways.

As noted above, the number of General and jurisdictional delegates are apportioned based on church membership. And membership figures are a key factor in determining the viability and number of districts, annual conferences, and episcopal areas in the church. But given all the variability in the ways members are created and membership rolls are maintained, how accurate is the data?

Which brings us back to Scott’s report on the rather dramatic increases he reports for minority groups and the lessons we might draw from their purported growth.

The UM Church is not particularly good at getting the big number right, let alone providing granular figures for distinct groups. Pastors, district superintendents, conference statisticians (typically a humble, hardworking pastor who has volunteered for the thankless post), and bishops are not trained census takers. And to believe that each year most pastors scrub their local church’s membership rolls, and then go on to decipher the racial and ethnic status of every member (a fair number of whom they may have never met) is to expect the unlikely. Some local churches do not ask the ethnic identity of their members and fail to track that characteristic accurately.

A comprehensive 2014 report by Lauren Arieux, a GCFA Research Fellow and Statistician, demonstrates how challenging it is to produce this type of data with consistency and reliability. While all of the minority groups in her report trend upwards from 1989 to 2013, the path is very inconsistent.

For instance, Hispanic membership is pegged at 60,900 in 2004, but one year later is reported to have fallen to 44,951. Four years later it shoots to 68,088.

And Asian membership is reported as 53,302 in 1995, then 44,940 in 1996, and back up to 53,731 in 1997.

African-American membership in 2001 is reported to be 409,432, one year later it has dropped to 371,203, but then rises the following year to 415,072. It is highly unlikely the church lost 38,229 African-American members in one year and then gained back 43,869 just one year later.

(It should be noted the figures for Caucasian membership go up and down as well.)

And none of this data actually comports with a Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study that Scott links to in his article. According to that report, Latino (or Hispanic) and Mix/Other each account for 2 percent of the UM Church’s membership, and Asian and Black each account for approximately 1 percent. The remaining 94 percent, according to Pew is Caucasian.

What all this likely reveals is not, as Scott would have us believe, dramatic and heretofore uncelebrated growth among minority groups, but a church steadily struggling to get better at something difficult to do under the best of circumstances: decipher with care and consistency the racial and ethnic composition of millions of people. And to complicate matters, the UM Church is trying to do it with people who are neither trained nor equipped for the task.

This is not to say the goal of ascertaining solid macro and micro membership numbers is not a worthy one; it is. Given the importance the church places on membership totals for apportioning representation and determining the viability of annual conferences and episcopal areas, it should strive for more consistent and accurate figures. But until it gets there, granular numbers should be handled with caution, and sweeping lessons drawn from them should be made with care.

Walter Fenton is a United Methodist clergy person and an analyst for Good News.

by Steve | Mar 20, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March-April 2017

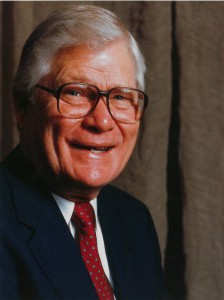

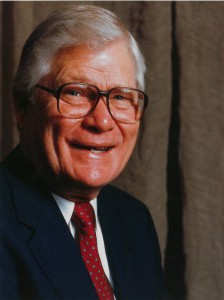

Rev. Rob Renfroe

By Rob Renfroe-

Facing reality can be painful. Especially when the only choices reality offers us are difficult, unsatisfying, or confusing. At that point there is a tendency to walk away from the problem emotionally and mentally in one of two ways. There’s the Scarlett O’Hara approach: “I can’t think about that right now. If I do, I’ll go crazy. I’ll think about that tomorrow.” Or we tell ourselves everything is going to be ok and make up some reason why we don’t have to act. In other words, we create a comforting myth that helps us sleep at night but that actually does nothing to resolve the issue. Either way, we deny reality and usually end up with a solution far worse than what might have been.

I’m afraid many United Methodists are still denying the reality of how deep our divisions run and how difficult a workable solution to our problems will be. I believe this because of the myths I hear people, many well-intended, clinging to and trying to persuade others to believe.

One long-standing progressive myth, recently restated by a retired bishop, is so obviously false that it’s hard to imagine anyone still holding on to it. It’s the idea that our differences over sexuality can be resolved through “the local option” – that is, allowing individual pastors to determine whether to marry same-gendered couples and permitting each Annual Conference to decide whether to ordain practicing gay persons.

Only persons who have been asleep longer than Rip Van Winkle was could find any solace in this illusion. More benign compromises failed to gain General Conference approval in the past decade. And more recently in Portland last May, after several of our leading pastors and our most influential administrative body, the Connectional Table, used all of their influence to promote such a plan, it was so soundly defeated in committee that it was not even brought to the plenary floor. The local option is dead. I pray that the Bishops’ Commission on A Way Forward will not waste precious time following our own Alices in Wonderland down that rabbit hole.

A conservative myth that needs to be dispelled is “maybe the progressives will leave.” It usually begins with the statement, “If they don’t like the way the church is, they should leave and start their own.” Sorry to burst your bubble, but this is a political battle. And in politics “should” has nothing to do with what people actually do. The progressive goal is to change the whole church, not create a progressive subdivision of the church.

An amicable separation (or as some have begun to call it “a new form of unity”) may be proposed by the Bishops’ Commission, but the progressives are not going to just up and leave on their own. Why would they? They just elected as bishop a married lesbian who has stated that she has performed 50 gay weddings. In the entirety of the Western Jurisdiction, in most of the Northeastern Jurisdiction, and in much of the North Central Jurisdiction pastors may marry gay couples and break the Book of Discipline with no consequences of any kind. A dozen annual conferences are on record that they will ordain practicing gay persons regardless of church law. So, why would progressives leave when they can do what they want to do, have continued access to general church funds, and can keep the name United Methodist?

“Well, we’ll write stricter legislation at General Conference and make it even harder for them to break the rules.” We have good policies now. Our problem has never been bad legislation; it has always been bad actors. You can be sure they will be just as disobedient to stricter rules as they are to the present ones.

“Then, let’s go nuclear. Let’s make the rules so that we can vote out any pastor, bishop, or congregation that breaks church law.” I understand this approach, but I find it less than realistic. Conservatives hold the line against gay marriage and ordination by the slimmest of margins every four years. It is a misguided myth to believe that the General Conference is going to give some governing body the authority to start excommunicating pastors, churches, and bishops. That’s not who United Methodists are. We are nice people, warm-hearted and generous of spirit. General Conference will never pass a proposal for some small group to be authorized to decide who’s a good enough Methodist to stay in the church and who’s not.

“But maybe in 20 years, we can ‘win.’” Faithful United Methodists are leaving our congregations every day because of the continuing battle over sexuality. People are tired of it and they’re walking away. Two large churches in Mississippi – one the 15th largest church in the denomination – have announced they are leaving. That’s in conservative Mississippi where no one is marrying gay couples and where the bishop upholds the Book of Discipline. In the Good News office, we regularly receive calls from pastors who are under pressure by their congregations, especially in liberal areas, to lead them out of the denomination.

If the Bishops’ Commission does not resolve this issue, there will be no “twenty years from now.” People will leave. Pastors will leave. Churches will leave. Conservative people, pastors, and churches. If the Commission does not come up with a solution, the church will be in so much chaos that the slow drip, drip, drip of faithful evangelical members leaving will become a roaring flood.

As evangelicals and traditionalists, we need to do some serious thinking about what it means to “win.” Win what? A church that 20 years from now could be so depleted in numbers that “a faithful remnant” would be a generous euphemism to describe what’s left? Winning is not holding onto a church that is a shadow of what it once was and what it could have been. A win for the Kingdom is coming out of the present mess with as many faithful Methodists as possible connected to each other and working together for the Kingdom.

One final myth is that “what’s at stake is the unity of the church.” We’re way past that. One bishop recently stated to his pastors, “Twelve of our annual conferences are in schism right now. They are unwilling to live by our covenant and that places them in schism.” Twelve annual conferences. That’s over one-fifth of the conferences in the United States and there are others who do not live by the Discipline, they just haven’t stated so publicly.

We are not a united church. Having the same name on our signs and the same logo on our letterhead does not make us a unified church. The bishops had their opportunity to work for the unity of the church by teaching our doctrines and enforcing our covenant for the past 50 years. Instead, many decided to be permissive parents allowing disobedience and rebellion, and others actually promoted such behavior. And sadly, few of our conservative bishops have banded together to speak out or call the rogue bishops to task. And the result, as it is with all families headed by permissive parents, is not unity but dysfunction, self-centeredness, and division.

Over a decade ago I told a group of bishops, tasked with creating unity within the church, “You may wish you had another issue to deal with other than sexuality. But this is the issue of your time that threatens to divide the church. You will either act in a way that holds us together or you will act in a way that guarantees our division. Either way, it will be on you.” Now here we are. And to be told by some of those same bishops that the unity of the church is now at stake – well, I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Look, the Commission is the game. Not stricter legislation in 2020. Not a local option. Not hoping or making the progressives leave. Those are myths and nothing more. Please do not be distracted by illusions that may bring comfort the way pleasant dreams do at night but that disappear upon waking. What the Commission recommends will either be based in reality or in wishful thinking.

Let’s make sure its members hear from us that clinging to or promoting myths and illusions – progressive or conservative – will not serve the church or the cause of Christ well. Reality may not be what we wish it was but it is what is. Let’s face it honestly and courageously with our eyes wide open.

Rob Renfroe is the president and publisher of Good News.

![Methodism in Cuba, Spirit-Filled and Overflowing]()

by Steve | Mar 20, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March-April 2017

Worship leader Lauren Smith Perez singing at Central Methodist Church in Havana, Cuba. Photo by Steve Beard.

By Steve Beard-

Within a Caribbean culture marked by Cold War skullduggery, economic scarcity, and vindictive secularism, the Methodist Church in Cuba stands out as a beacon of spiritual freedom, miraculous signs and wonders, unexpected blessings, and salsa infused worship. Not only has vibrant Christianity survived some of the darkest decades of Cuba’s history, it is a thriving testimony to the profound hope found at the roots of the faith.

“Young people in Latin America have spent a long time learning a language that is different than the language of God,” said the Rev. Guillermo Leon Mighthy, illustrating the prevailing way of thinking in Cuba.

“By the age of 18, they have heard more than 80,000 times these five phrases: (1) ‘I don’t know,’ (2) ‘There isn’t any,’ (3) ‘I don’t have any,’ (4) ‘I can’t,’ and (5) ‘It’s not easy.’ Five negative phrases; nothing positive,” said Leon. “This is not the language of the Bible.”

Leon is the 41-year-old lead pastor of the Central Havana Methodist Church in one of the grittiest neighborhoods in the Cuban capital. As a former professional soccer player and past leader of Methodist youth in Cuba, Leon has a spiritual counterattack for each of these phrases.

“First, the Bible never says that we don’t know. We know who we are, we know what we have, and we know the One who is with us. Second, yes there is; in God there is hope. In God there is healing. In God there is blessing,” said Leon, who is also the district superintendent of Havana.

“Third, yes we have. God says he is our shepherd and we will lack nothing. God says that whatever we lack we will receive in riches in his glory,” he continues. “Fourth, yes, we can do it. The apostle Paul says in Philippians that we can do all things in Christ who strengthens us. Lastly, with Christ it is easy, because Christ helps us. Nothing is impossible with God.”

The falling of the fire

Hope and anticipation are common themes in Leon’s preaching, along with spiritual warfare, victory, overcoming, healing, and blessing. These are also the repeated themes in the Cuban Methodist pulpits and the narrative of testimonies delivered during services. The spiritual dynamic behind the growth of Cuban Methodism is the “movement of the Holy Spirit,” said Pastor Aylen Font Marrero, a 29-year-old staff member of the Methodist Cathedral of Holguín, 450 miles east of Havana.

According to the latest information provided by the Methodist Church of Cuba, there are 410 churches and 927 missions (churches in formation). With

Pastor Adria Nuñez Ortiz delivering a message at Central Havana Methodist Church. Photo by Steve Beard.

approximately 46,500 members, there are about twice that number involved in the ministry of the denomination in different ways.

Although the personalities and styles of each congregation may differ, Font believes that Cuban Methodists are unified in “seeking God, the movement of the Holy Spirit, the falling of the fire and anticipating the glory of God to descend.” The primary focus of each congregation is “the love of God for the people of God. This is what we want to really see and experience and see grow,” she said.

The embers of this revival fire have been stoked since the 1970s, reports the Rev. Dr. Rini Hernandez, district superintendent in the Florida Annual Conference. Desperate times called for desperate measures. Methodists all over Cuba were participating in all night prayer vigils, reports Hernandez. The outgrowth of their prayers were miraculous signs and wonders, including speaking in tongues, physical healing, deliverance from spiritual oppression, and being physically overwhelmed by the power and presence of God in their meetings.

“We did not know it was Pentecostal,” Hernandez told Good News. “We were just asking God to fill us with the Holy Spirit.” Along with the outpouring of supernatural occurrences, these Methodists experienced a holy boldness that has characterized their singular focus on sharing their faith. “We lost all fear of repercussions and committed ourselves to share the good news of Jesus Christ with the Cuban people, one life at a time,” he recently wrote in an article for the Florida Annual Conference. “The Holy Spirit’s fire spread out to the local churches, youth camps, and almost every event in the life of the church.”

Heart-warming experience

In an interview with Bishop Ricardo Pereira in conjunction with my first visit to Cuba more than 16 years ago, he told of his special experience with the Holy Spirit on October 18, 1984, many years before he became bishop. “At that time I had two young men in my church —14 and 16 years old. They had read about John Wesley and his ‘heart-warming’ experience,” Pereira said.

“That night, at 8 o’clock they knelt down in the church and said to me, ‘Pastor we are not going to get up from here until we have the same experience that John Wesley had.’” Pereira told them that they were confused. “I don’t think it works that way. I have been told that not everyone receives the same experience.” Nevertheless, these boys were going to pursue a blessing from God. Pereira said that he grabbed one of the boys, but he said, “Pastor I will not get up from here.”

Pereira was angry. “I slammed the door and went home and started watching television,” he admits. “But something was stirring in my heart, telling me, ‘Pastor you are not doing right. How can you allow your members to pray by themselves? Why don’t you go and keep watch with them?’”

He walked back to the sanctuary and said to them, “See, you have not received anything.” The boys continued asking God to give them the power to evangelize. At 11 o’clock he told them, “It is very late. Why don’t you begin again tomorrow?”

“No pastor,” they said, “we are not going to get up from here until we receive the touch of the Spirit.” At 12:04, Pereira reports that the boys had an “explosion of light in their faces and great joy in their heart.” After their experience, Pereira said: “I was so afraid that I knelt next to them and said, ‘Okay, I won’t get up until He fills me up, too.’ I wept and asked God to forgive me. And I said, ‘Lord I want you, too. I have been preaching the gospel, doing the best I could, but if this joy is real, if you can give that explosion in the hearts of my two members, you can give it to me, too.’

“At 3:00 a.m. we were all like mad people, speaking in tongues. I woke up my wife so that I could tell her that I too had this joy in my heart.”

Renewed Methodism

The Rev. Guillermo Leon Mighthy holds the microphone for trumpet player Jorge Lázaro Corrales Estradas. Photo by Steve Beard.

Although both share in an experiential and supernaturalist faith, Pentecostal denominations such as the Assemblies of God believe that speaking in tongues is the “initial evidence” of receiving the baptism of the Holy Spirit. That is not a doctrinal distinctive for Methodists. Nevertheless, Methodist services in Cuba are unapologetically charismatic. The framework for theology and ministry within Cuban Methodism was not imported from other denominations, but is an organic expression of their own unique divine encounter.

The Cuban experience mirrors the religious trend of its neighbors. In the latest study of 18 Latin American and Caribbean countries and one U.S. territory (Puerto Rico), Pew Research found that two-thirds of Protestants (65 percent) identified as Pentecostal Christians either through denominational affiliation or personal self-identity.

Sociologists pair Pentecostals and charismatics into the category of “renewalists” when studying international religious trends. As the fastest growing spiritual movement, renewalists account for one-fourth of all global Christians with upwards of 500 million adherents. According to the World Christian Database of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, Brazil has the highest number of renewalists, followed by the United States, China, Nigeria, India, and the Philippines.

As Professor Philip Jenkins points out in his ground-breaking work, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity, believers outside the United States take the Bible very seriously. “For Christians of the Southern Hemisphere, and not only for Pentecostals, the apostolic world as described in the New Testament is not just a historical account of the ancient Levant [sections of the Middle East], but an ever-present reality open to any modern believer, and that includes the whole culture of signs and wonders. Passages that seem mildly embarrassing for a Western audience read completely differently, and relevantly, in the new churches of Africa or Latin America.”

At the outset of the Cuban revolution, the late Fidel Castro used to define the boundaries of cultural engagement to the intellectuals and artists: “Inside the revolution, everything. Against the revolution, nothing.” Within revival, the Methodist Church has transfixed and transformed – redeemed, perhaps – that kind of singular focus to a pinpoint: Cuba for Christ.

High voltage worship

Even non-church going observers would recognize something combustible and dynamic taking place in a Cuban worship service. This is not the place to be if one has been lulled into expecting a predictable 55-minute morning service with two Victorian-era hymns, a children’s sermonette, a choral anthem, a homily, and tidy benediction.

“We worship God with so much passion,” said Pastor Adria Nuñez Ortiz, “we give him praise with all we have in our hearts. We have so much love for God because we understand that he has done so much for us. Everything we do for him is nothing in comparison to what he has done for us.” Nuñez is associate pastor of Central Havana Methodist Church and married to Pastor Leon. She is also a songwriter, musician, and leader of their high-energy choir.

The worship time is unmistakably Caribbean. “As in biblical times, Cuban Methodists praise the name of the Lord and dance with all kinds of instruments and shouts of joy,” Bishop Pereira told me not long ago. There is a jacked-up salsa beat with a sliver of hip-hop and drums, congas, guitars, bass, trumpets, and trombones. If you solely associate Cuban music with Buena Vista Social Club, there is a brand new galaxy of sound in the church. The worship is frenetic, physical, ecstatic, electrifying, and emotional.

With a smile, one pastor told me that the “jumping does not draw the Holy Spirit, but jumping is the response when the Holy Spirit falls.”

For Nuñez, the pogoing up and down in worship is a simple expression of joy. “We rejoice every time we think about what God has done for us,” she said. “Specifically in our context of central Havana, many people were drug addicts, idol worshippers, prostitutes and God took them out of that way and saved them. The Bible says that the one who is forgiven much, loves much. And when somebody pays a huge debt for you, then expressions of joy and happiness come out of your heart and that’s what’s happening in Cuba.”

New day in Cuba

Needless to say, many things have changed in Cuba since my first visit in 2000. Netflix is streaming (for those with credit cards); the online home rental business Airbnb is now available to foreigners, the black market emporiums are hiding in plain sight, and the Rolling Stones played last year before 500,000 in Havana in a free concert a few days after President Barack Obama’s controversial visit. With the average Cuban making less than $20 a month, there still isn’t expendable income for luxuries such as high-dollar rock concert tickets.

Cell phones are omnipresent (a vibrant black market), but the internet is spotty and frustratingly slow. Private enterprises are still in infancy stages, as one might expect in one of the last remaining Communist countries. There is, understandably, a strand of “forbidden island” allure for Americans to explore Cuba as more avenues open for tourism. Many visitors simply hit the Ernest Hemingway hot spots, buy cigars, rum, and a Che Guevara t-shirt, cruise around in a 1952 pink Cadillac convertible taxi cab, and then drink mojitos on the pristine beaches.

Dr. David Watson of United Theological Seminary preaches in Santiago de Las Vegas Methodist Church as Pastor Aylen Font Marrero translates the message. Photo by Steve Beard.

For Professor David Watson, however, the experience is all about plunging his students into the eye of a revivalistic tornado. “A lot of our seminary students have never experienced what spiritual renewal looks like, and when they come here they get to be a part of a very powerful Spirit-filled revival,” said Watson, the academic dean at United Theological Seminary. Watson has brought students to Cuba from the Dayton, Ohio, seminary for the last three years.

“One of the ideas behind our seminary’s emphasis on church renewal is that all renewal – individual, local church, or church universal – is the work of the Holy Spirit. That is certainly the case in the Cuban Methodist revival,” he observed. “We want our students to be exposed to and learn about what it looks like when God shows up in a powerful way in the life of a congregation or denomination.”

Amanda Moseng is one of those seminary students, soon-to-be a provisional elder in the West Ohio Annual Conference. Her trip to Cuba was sparked by a divine healing she experienced at a Holy Spirit conference hosted by United Seminary. While in Cuba, Moseng tirelessly prayed for healing and blessing for those who came forward at the end of each of the services. Not raised as a charismatic, the Cuban scenario was new, but she adapted with deftness and enthusiasm.

Moseng’s own healing encounter is the catalyst behind her faith to confidently pray for “healing in people and to open myself to let the Holy Spirit work in whatever way the Holy Spirit wants to manifest,” she said. Prior to her trip to Havana, she had never prayed for healing for someone else. She now has a “boldness of faith that only God grants, that only comes from the Spirit.” Moseng also had the unique opportunity to preach in the Central Havana church on “holy boldness” to an attentive congregation. “I’m just so humbled that God would choose me to do those things, that God would use me for that. I will be eternally grateful for what I’ve experienced here,” she said. “I’ve been transformed in ways I could never have imagined and I will leave here with a sense of boldness and faith that’s greater than I’ve ever had.”

Finding wealth in Cuba

For the last 28 years, the Rev. Jaime Nolla has made a yearly pilgrimage to Cuba. “When you see people who either walk for miles, travel on the back of a platform truck, or travel in an overloaded, very old bus, standing because of the lack of space, to get to a crowded church anticipating to experience the presence of God, your heart is moved in ways you cannot describe with words,” said Nolla, a retired United Methodist pastor and former district superintendent in the Wisconsin Annual Conference.

Nolla was one of the clergypersons standing in the front of the 500 men and women jammed into the sanctuary of the Vedado Methodist Church in downtown Havana waiting to be anointed with oil. The bustling and energetic congregation worships in a striking art deco church with loud praise music spilling out from the open doors and windows near the University of Havana. The expectancy and desire was palpable as those in seemingly never ending lines waited patiently in an attitude of prayer for this blessing.

Nolla’s numerous visits over such a lengthy period of time have afforded him opportunities to see innumerable Methodist congregations across the length of the island (more than 700 miles long).

“Many of these people come dressed with the one or two outfits they own because of the poverty on the island. However, none of the obstacles that would stop people from coming to church in the United States are big enough to stop them from coming to church,” he told Good News. “We are thankful to God for the commitment and dedication second to none that we have seen and experienced.”

“When you live in a place where there is extreme poverty, the response of the people is to find wealth in other ways,” observed the Rev. Rebekah Clapp, one of my travel mates and translators in Havana. “For Cubans, that spiritual wealth has become a response to that.” Clapp earned her M.Div. at United Theological Seminary after living in Nicaragua, and is currently working on her Ph.D. in intercultural studies at Asbury Theological Seminary.

“Because of the reality of spiritual forces that they interact with, Christians respond with language of victory, language of overcoming,” she continued. “They have victory in their lives in Christ over and against spiritual forces, over and against the powers of the idolatrous religions, over and against the work of the devil, and also over and against the socioeconomic and political reality in which they live. They can respond to it by saying, ‘I have life in Christ, I have power in the Holy Spirit, and I have victory.’ That gives them hope, that gives them purpose.”

It may also go a long way in explaining how the Methodist Church has been a sustained oasis in the spiritual desert of Cuba’s soul for the last 50 years.

Marking his 25th year, Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

![Methodism in Cuba, Spirit-Filled and Overflowing]()

by Steve | Mar 20, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March-April 2017

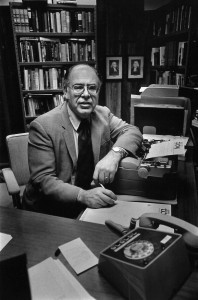

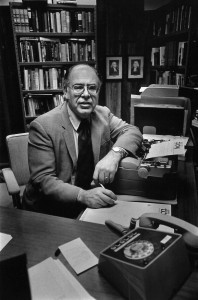

Archive: Shaping our Theological Core

Evangelist Ed Robb preached a sermon on seminary education that sparked a controversial debate.

It was the fiery speech about seminary education given by Dr. Ed Robb Jr., an outspoken evangelist from Texas, that caught the attention and ire of Dr. Albert Outler, preeminent Wesleyan scholar at Perkins School of Theology. Through the eventual friendship of these two unique and legendary figures within United Methodism, nearly 150 Wesleyan scholars committed to the historic faith have since earned PhDs or ThDs through A Foundation for Theological Education (AFTE).

The foundation affirms the divine inspiration and ultimate authority of the Scriptures in matters of faith and practice; incarnation of Jesus Christ as fully God and fully human; necessity of conversion as a result of repentance from sin and faith in the Lord Jesus Christ; the church is of God and is the body of Christ in the world; and the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper are means of grace.

During the 1970s, Good News focused upon seminary education, launching Catalyst (now published by AFTE), funding worldwide missions, and engaging “theological pluralism” with the “Junaluska Affirmation,” an orthodox statement on Wesleyan theology. Good News requested time before the Association of Deans and Presidents of United Methodist Seminaries to present its concerns in more detail. This request was denied. However, the association did indicate receptivity to visits by seminary students, faculty, and administration.

As a result, representatives from Good News were able to have on-campus discussions with representatives of ten official United Methodist seminaries. Two seminaries turned down the request for dialogue.

As Good News celebrates 50 years of ministry within The United Methodist Church, we share the following report of Ed Robb’s speech and the creation of the Junaluska Affirmation by Dr. Riley B. Case, author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History, as a testimony to the faithfulness of men and women who sacrificially prayed for and contributed to the cause of renewing United Methodism.

–Good News

By Riley B. Case

The spirit at the 1975 Good News Convocation at Lake Junaluska, North Carolina, was exhilarating, but it was intended to be more than just an evangelical family reunion. Good News was in the business of renewal, and The United Methodist Church was experiencing very little renewal. The reports were discouraging:

• In the church’s new structure, power was concentrated in the General Board of Global Ministries, which, under domination of the Women’s Division, had declared itself on behalf of liberation theology. The Commission on Social Concerns in the former Methodist structure, controlled by persons many considered social extremists, had been elevated to the status of a board, while evangelism and education had been diminished by being subsumed as divisions under the Board of Discipleship. Youth ministry was disintegrating; curriculum sales were plummeting.

• The Church’s new doctrinal statement was serving further to undermine the Church’s historic doctrinal heritage. The seminaries were still not open to evangelical presence.

• The former Evangelical United Brethren were finding that the merger was not a marriage of equals, but a corporate takeover. EUB practices and beliefs, such as freedom of conscience in matters of baptism and infant dedication, contrary to reassurances given before merger, were being scuttled by the new Church.

These discouraging developments were being reflected in dramatic reversals in membership, worship attendance, and Sunday school enrollment.

Dr. Ed Robb’s keynote address at the 1975 convocation spoke to the evangelical discontent with the seminaries. The presentation, entitled “The Crisis of Theological Education in The United Methodist Church,” linked the problems of the Church to leadership and the problem of leadership to the seminaries: “The question is, who or what is responsible for this weak leadership. I am convinced that our seminaries bear a major portion of the responsibility. If we have a sick church it is largely because we have sick seminaries.”

Among the litany of failings and shortcomings linked to the seminaries, Robb further charged: “I know of no UM seminary where the historic Wesleyan Biblical perspective is presented seriously, even as an option.”

Robb asked (1) that two seminaries be entrusted to evangelical boards of trustees and continue as United Methodist seminaries; (2) that in the spirit of inclusiveness, every United Methodist seminary invite competent evangelicals to join the faculties; and (3) that greater support be given to established evangelical seminaries, especially those in the Wesleyan-Arminian tradition.

The seminaries, and the Church’s Board of Higher Education and Ministry, if they even were aware of the Good News critique, were not inclined to treat the Robb challenge with any seriousness. No established “leaders” in the Church would ever even consider allowing evangelicals to operate a United Methodist-related seminary, and no seminary would allow such a radical shift in focus. And, these “leaders” would argue, the seminaries were already inclusive and diverse. Furthermore, there was absolutely no interest in supporting non-United Methodist schools, especially evangelical schools.

From the perspective of the institutional church and the seminaries, Good News was a reactionary throwback to a dead past. Though the convocation and Robb’s address were well reported, especially by The United Methodist Reporter, there was little denominational response to the events of the convocation – with the exception of Albert Outler, professor of Historical Theology at Perkins School of Theology. Dr. Outler did note the address and was offended by the Robb charges, especially the accusation that there was no seminary where the Wesleyan biblical perspective was treated seriously, even as an option.

Outler, too, was longing for United Methodist renewal. In many respects, Outler was “Mr. United Methodist” of the 1970s. He had chaired the Study Commission on Doctrine and Doctrinal Standards for The United Methodist Church. He had lectured bishops and represented the Church in ecumenical councils. In his lectures at the Congress on Evangelism in New Orleans in 1971, Outler recognized a growing evangelical renaissance, the sterility of liberalism, and sought to call the Church to an authentic Wesleyan theology.

In the lectures, however, Outler was not pleased with much of evangelicalism, especially with that offered by Good News: “[T]hese fine old words [‘evangelical,’ ‘evangel’] have … generated many a distorted image in many modern minds – abrasive zealots flinging their Bibles about like missiles, men (and sometimes women!) with a flat-earth theology, a monophysite Christology, a montanist ecclesiology and a psychological profile suggestive of hysteria.”

It is no wonder Outler reacted strongly to Robb’s address. In a letter to The United Methodist Reporter, Outler expressed his unhappiness: “I was … downright shocked by one of the quotations. It is sad that a well-meaning man should lodge a blanket indictment against the entire lot of United Methodist theological schools in terms so unjust that they are bound to wreck incalculable damage to the cause of theological education in the UMC – which is, as we all know, in grave enough peril already ….

“What shocked me, though, was Dr. Robb’s reported declaration: ‘I know of no United Methodist seminary where the historic Wesleyan biblical perspective is presented seriously, even as an option.’ The point, of course, is that, since Dr. Robb knows of Perkins, he has said, by strict logical entail, that the historic Wesleyan biblical perspective is not presented seriously at Perkins, ‘even as an option.’

“Now, either the phrase ‘historic Wesleyan biblical perspective’ means something that neither I nor other Wesley scholars – here and elsewhere – understand or else this accusation is simply false …. I can think of many ways in which a much needed, candid debate about Methodist theological education could have been stimulated and helped ahead; Mr. Robb’s way resembles none of them.”

Even Spurgeon Dunnam, editor of The United Methodist Reporter, was taken aback by the forcefulness of the Outler letter and contacted Robb for a response. Robb wrote a response but believed more was needed. Robb called Outler and asked if he might come to see him. Outler, according to Robb, had to think about that request for awhile before he gave grudging consent. And so it was that Ed Robb and Paul Morrell, Good News board member and pastor of Tyler Street Church in Dallas, made their call on Outler at Perkins School of Theology.

Dr. Albert Outler of Perkins School of Theology in Dallas.

Outler gave his version of the visit in an article printed in The Christian Century: “It was … downright disconcerting to have Dr. Robb and some of his friends show up in my study one day with an openhearted challenge to help them do something more constructive than cry havoc. Needless to say, I’ve always believed in the surprises of the Spirit; it’s just that they continue to surprise me whenever they occur!

“Here, obviously, was a heaven-sent opportunity not only for a reconciliation but also for a productive alliance in place of what had been an unproductive joust. Moreover, as we explored our problems, some unexpected items of agreement began to emerge.”

Thus began an unlikely friendship and alliance that would eventually lead to the establishment of A Foundation for Theological Education (AFTE). Outler’s friends in the academic world were willing to trust Robb because of Outler. Robb’s friends in the evangelical world were willing to trust Outler because of Robb.

Outler would later comment that AFTE was the most satisfying achievement of his life. In his own affirmation of Outler, Robb and the AFTE board, and not Perkins or Southern Methodist University, initiated the campaign to raise $1 million to endow the Albert Outler Chair of Wesley Studies at the seminary. The money was raised and the chair established.

Outler’s pluralism

Albert Outler, however, was not universally appreciated by Good News, primarily because of the 1972 doctrinal statement affirming “theological pluralism.” In some circles it was also known as the “Outler Statement.”

Good News had, from its inception, believed that the recovery of classical Wesleyan doctrine was the key to denominational renewal. Charles Keysor charged that the feature of “doctrinal pluralism” meant that “anybody was free to believe anything – with no negative limits.”

The great Methodist middle, however, was at best ambivalent, and in some cases downright hostile, to the suggestion that renewal in the Church was directly linked with a recommitment to historic doctrine. The arguments depreciating doctrine took several forms:

• Methodism was never a confessional church;

• Wesley had said, “If your heart is as my heart, give me your hand,” suggesting that Methodism was primarily a religion of experience;

• the way a Christian lives is more important than what a Christian believes;

• doctrine divides; and

• the emphasis on correct belief is judgmental and unloving.

A time of turmoil in politics, moral traditions, and social customs, the 1960s also brought with it a time of theological confusion: existentialism, personalism, fundamentalism, Death of God theology, process theology, and liberation theologies.

With the merger of The Evangelical United Brethren Church and The Methodist Church in 1968, the matter of stated doctrine had to be faced. Whether or not anybody believed in them – or even knew they existed – doctrinal statements had been carried in every Discipline of all the predecessor denominations from the first Methodist conference in 1784. What was now to be done with these statements, specifically the Articles of Religion of The Methodist Church and the Confession of Faith of the EUB Church?

The task was handed to a commission headed by Outler and board and agency representatives, several prominent pastors and laypersons, and a heavy preponderance of seminary professors, including outspoken liberals.

Good News, though still a fledgling movement when the commission was established, asked to participate in the discussions. There was not even a response to the letters that asked for Good News involvement. For his part, Outler was devoted to the commission and its task. He was also, perhaps more than any other person, aware of the problems the commission faced:

• Both churches, the Methodist and the EUB, had stated doctrinal standards, even though there was some discussion as to what precisely the standards were. For Methodists, the standards started with the Articles of Religion. But did they include Wesley’s sermons and his Notes Upon the New Testament?

• The doctrinal standards had been widely ignored, and even scorned, for a number of years. They were almost never referred to in Methodist seminaries.

• The scuttling of the EUB and Methodist statements, or the combining of the two, even if desirable, would probably not be possible, because of the restrictive clause in the constitution of the Methodist Discipline that stated: “The General Conference shall not revoke, alter, or change our Articles of Religion or establish any new standards or rules of doctrine contrary to our present existing and established standards of doctrine.”

The Outler solution was ingenious. Do not tamper with the restrictive clause (this would be a long, complicated, unproductive, and probably unsuccessful constitutional engagement), but write an additional statement that would interpret the doctrinal standards, placing them in historical perspective, and letting them inform the present task of theologizing even as they did not inhibit that task. Then call the Church to a new challenge to theologize and, in the process, to restate the doctrinal tradition while all the time making doctrine relevant for the present time.

The emphasis of the new statement would not be on content, that is, on the actual teachings of Methodism and Christian faith, but on process, that is, how the Church went about determining what it believed: “In this task of reappraising and applying the gospel, theological pluralism should be recognized as a principle.”

The 1972 General Conference approved the report of the Doctrinal Commission 925-17 without amendment and without discussion. No Good News voice, nor any evangelical voice for that matter, nor any voice from any perspective, even raised a question about the report or the ideas therein. After accepting the report that asserted that The United Methodist Church was not a creedal or confessional church and that pluralism was the guiding principle that would inform future doctrinal discussions, the conference moved immediately to “the social creed,” and social principles in an extended floor debate that lasted six hours. During that time, the thought that diversity or pluralism might also apply to the Church’s social stances was not expressed even once.

The Good News board was devastated by the lopsided approval of the doctrinal commission’s report and the fact that it was received so nonchalantly.

The summer 1972 issue of Good News carried a twelve-page report on General Conference written by Chuck Keysor. Five of the pages were devoted to the doctrinal statement. Quoting reports in Engage magazine and the Texas Methodist, he also argued that the statement was a revocation and alteration of the present doctrinal standards and was thus in violation of the restrictive rule in the Discipline.

Dr. Outler was scandalized by the Good News evaluation. In true Outler-style, he wrote Keysor: “Your surprisingly harsh and reckless comments on the new UMC Doctrinal Statement … have left me utterly appalled. I had not, of course, ever hoped for your positive approval, but I really had thought you might have been willing to recognize our positive efforts to make room for both conservative and liberal theological perspectives in the United Methodist Church. … There is, therefore, something tragic in your reckless and total rejection of us, since it forecloses any possibility of further meaningful dialogue. This, in turn, can only result in mutual loss, to all of us and to the church as well.”

Keysor responded in true Keysor style: “We find it ironic to hear you saying that our editorial shuts the door to dialogue. As I have already named, there was no dialogue from you until after the editorial, so it seems that publishing more editorials is the way to increase dialogue.”

Good News was not opposed to pluralism or diversity as such, but insisted that pluralism needed to operate within carefully defined limits, or an essential core of truth. Otherwise, nothing would be unacceptable as United Methodist teaching. Outler and the commission insisted that there was an essential core but never defined what it was. To Good News and others, this was like the proverbial emperor’s new clothes; one might claim to see them, but they weren’t really there.

Outside observers as diverse as Christianity Today and Time magazine understood this quite well. The Time magazine report of the General Conference noted: “The Outler commission’s solution qualifies the traditional creeds – Wesley’s Articles and the E.U.B. Confession of Faith – with explanatory statements warning that they should be interpreted within their historical context. The statements maintain that Wesley and the E.U.B. patriarchs made “doctrinal pluralism” a major tenet and held to only a basic core of Christian truth – but the statements stop short of specifying what that core was.”

With its stand clearly taken, Good News was willing to stay the battle. As Keysor editorialized in the summer issue of Good News in 1972: “What are evangelicals to do, in the aftermath of Atlanta? Many are quitting, feeling that the United Methodist Church has abandoned and betrayed Christ, the Gospel and its members.

By Charles W. Keysor, Founding editor of Good News

“Good News feels deep sorrow and pain at the exodus of these brothers and sisters in Christ. We do not condemn any person for following God’s leading, but we feel strongly that God calls us to remain. This has been our motive from the start…. To separate or not to separate, that is the basic issue. And so we feel it desirable to share with readers why we believe the most important place for evangelicals is inside the United Methodist Church.”

Keysor’s reasons for staying reflected a remnant kind of thinking: “In the past (God) has worked miracles through tiny remnant groups which fear only displeasing the One who has called them – the One whom they know as Father. Who cares if we are a small minority? Numbers and success are pagan preoccupations. To gain control of the denominations means nothing; to be faithful to Jesus Christ means everything.”

Junaluska Affirmation

Chuck Keysor and Albert Outler had an intensive two-hour conversation when Outler came to Asbury Seminary in March 1974 to deliver a series of lectures on Wesleyan theology. In a detailed account of the conversation shared with a few members of the board, Keysor offered his impressions of Outler reacting to Good News concerns: Though Outler strongly believed in a core of irreducible doctrinal truth, he also believed that attempts at doctrinal definition “always result in inadequate conceptions of ultimate realities” (propositional statements demanding allegiance smacked of fundamentalism). He admitted, basically, that he was not interested in a specific of “core” essential doctrine, even though he believed the Church could refer to such a core.

Outler, however, was at least pleased that someone was willing to discuss doctrine and offered his own suggestions as to the sorts of actions Good News might pursue.

l. Good News could test the seminaries’ resistance to pluralism by underwriting the education of several outstanding young scholars who would take degrees at such institutions as Yale, Chicago, or Oxford in such areas as patristics, historical theology, and New Testament and, then backed by impeccable credentials, go to the Board of Higher Education and ask if there is any discrimination because of their conservatism (this would soon become the strategy of A Fund for Theological Education [AFTE]).

2. If the Church really wanted a descriptive statement of the “core” of essential United Methodist doctrine, it could do so by amending or altering the present statement with a 51 percent vote of the General Conference (this, in fact, would soon become the Good News legislative strategy in coming General Conferences).

3. Outler’s intent in the 1972 statement was to sketch broad theological generalities and encourage “theologizing,” in which identifiable groups in the Church would delineate their own essential core – what they would be willing to die for.

It was this third suggestion that gave additional impetus to a Good News effort, already being discussed and planned, to offer a contemporary evangelical statement of the essential core of Wesleyan doctrine for United Methodism. To do this, Good News called upon Paul Mickey, Associate Professor of Pastoral Theology at the divinity school at Duke, to lead a committee to draft a statement. Good News leaders such as Chuck Keysor, James V. Heidinger II, myself, and Lawrence Souder were joined by Dr. Dennis Kinlaw, president of Asbury College and Dr. Frank Stanger, president of Asbury Seminary, to draw up the statement.

The Junaluska Affirmation would be an evangelical response to the 1972 doctrinal statement’s invitation for groups to engage in theological discussion and affirmation, seek to identify the “core of doctrine” that the 1972 statement alluded to but never defined, and serve as a rallying point for evangelicals in the Church.

Before the final draft, the statement was shared with Albert Outler. He was obviously pleased that at least one group was taking the 1972 statement seriously enough to draw up a doctrinal statement. In response, Outler wrote: “Thanks for that copy of the ‘draft statement’ of ‘Scriptural Christianity for United Methodists.’ I’ve read it with care and real appreciation. This is an important response to that invitation … I welcome the venture, even as I have found it interesting and edifying. Power to the project – especially in its tone and temper!”

Outler continued with an eight-page critique of the statement. His critique perhaps said more about his own theology than the work of the committee. Outler argued that the approach of the statement, that is, the organizing of essential doctrines around themes of systematic theology (sin, God, atonement, Jesus Christ) was not Wesley’s approach, who rather located the “essentials” in the proclaiming of the holy story.

The statement was made available at the 1975 Good News Convocation at Lake Junaluska, where it was discussed in small groups, adopted by the assembly gathered, and became known as the Junaluska Affirmation.

The United Methodist Reporter editorialized positively on the Junaluska Affirmation and printed it in full. UMCom, the official United Methodist news service, commented briefly that the “affirmation” had been adopted and added remarks from Paul Mickey about the need for ‘theological clarity in a time of theological confusion” and from Good News referring to the doctrinal standards and the ancient creeds as the “foundation for historic faith.”

There was some disappointment on the part of Good News that the affirmation failed to stir up either reaction or critique or comment from the larger Church. It was pointed out, however, that except for the bishops – given the charge in the Discipline “to guard … the apostolic faith” – no board or agency or group in the Church felt ownership or responsibility for doctrine. It was not so much that the general Church agreed or disagreed or affirmed or denied the Good News doctrinal effort. It was rather that it just did not care that much.

Later, the September 1975 issue of Interpreter magazine carried an editorial by Roger Burgess entitled “Has Good News Become Bad News?” Burgess did not critique the Junaluska Affirmation but was uneasy that Good News should draw up a statement in the first place. He concluded: “I find it hard to discover much that is constructive or loyal in these actions and proposals.”

As far as Good News was concerned, the Burgess comments were a misreading of the intent of the Junaluska Affirmation and of the purpose of Good News. But for once, Good News was secure enough it did not need to be defensive about the accusations of the editorial. It would direct its energies from this time forth not needing to define who it was, but in understanding and seeking to bring renewal to The United Methodist Church.

And the task, at least as it related to doctrine, was formidable. The general Church, already in a state of doctrinal confusion, seemed to be able to make no sense out of the 1972 statement. The attempts to clarify seemed only further to obfuscate. In 1976, the General Board of Discipleship published the pamphlet “Essential Beliefs for United Methodists.” It was to be an attempt to interpret to local churches and individuals the 1972 doctrinal statement.

The pamphlet managed to feature “essential beliefs” without the first mention of doctrinal standards or of the Articles of Religion or the Confession of Faith or of the sermons of Wesley. The one belief that seemed more essential than all others was the belief that “our strength comes through unity in diversity rather than through rigid uniformity.”

If there were “essential beliefs,” they were what we were to formulate for ourselves (the opening sentence was, “Our beliefs grow out of our experiences”), based on the quadrilateral: Scripture, Tradition, Experience, and Reason. These core beliefs evidently had nothing to do with Christ’s death on the cross for our sin or, for that matter, Christ’s death on the cross for any reason. Nor did it refer to the Resurrection, to salvation, justification, sanctification, heaven or hell, or to the New Birth. At least none of these were even mentioned.

The pamphlet was obsessed with the importance of the quadrilateral, and that discussion took twelve of the sixteen pages. It spent time with sacraments and mentioned creeds, but only with the discounting qualification that “the living God cannot be reduced to or contained in any creed.”

But, according to the pamphlet, the Church was not without stated beliefs. United Methodists did have agreement, if not about doctrinal beliefs, then on the social principles. “Essential Beliefs for United Methodists” closed with the Social Creed prefaced with the words: “Our Social Creed provides a summary of our beliefs as United Methodists.”

Good News had a long and laborious task ahead of it.

Riley B. Case is the author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History (Abingdon). He is a retired United Methodist clergy person from the Indiana Annual Conference, the associate director of the Confessing Movement, and a lifetime member of the Good News Board of Directors. This essay is adapted with permission from Evangelical & Methodist.